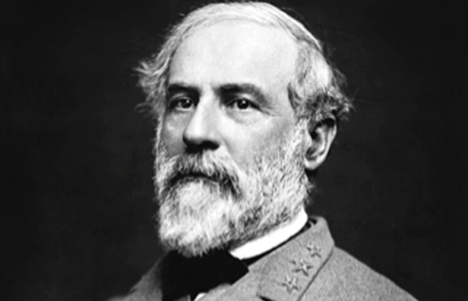

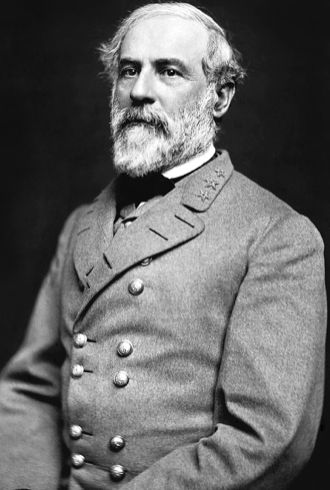

The American Civil War was a watershed moment in American history, a four-year battle that was the culmination of decades of hostilities over the issue of slavery. In its final years, the War pitted two Generals against each other, Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee—fierce warriors whose armies engaged in a devastating war of attrition that led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of young men. Leading the Confederate Army, General Lee proved to be a brilliant strategist and relentless warrior, who brought the battle to the Union Armies despite an increasingly dwindling supply of men and material in the later years of the war. In the early years, he led his men to victory in the Second Battle of Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. He was defeated, however, at the Battle of Gettysburg, and later fought inconclusive battles in 1864-65 at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and the Siege of Petersburg. He was finally surrounded at Appomattox, and surrendered his troops to Grant on April 9, 1865.

Although historians have condemned Lee for his support for the institution of slavery (he was a slaveholder himself), his public and private comments when the war commenced offer a more complicated picture of his thinking about the “war to free the slaves.” When he turned down an offer to command the Union Army, he said that he was doing so in order to return to Virginia to defend his ancestral homeland. Previous to that, however, he was known to be an advocate for the preservation of the Union, despite the powerful voices in Virginia and other Southern States advocating for secession. In this respect, Lee may have been a reluctant warrior. Indeed, in an 1856 letter, he said that “slavery as an institution is a moral and ethical evil in any Country.” He also said, however, that “the painful discipline they are undergoing is necessary for their instruction as a race,” and beseeched that “how long their subjugation may be necessary is known and ordered by a wise and Merciful Providence.” Lee’s conflicting views on slavery were, sadly, shared by many Americans at the time, both North and South.

Throughout his life, Robert E. Lee was a proud and dedicated leader of men. He came from a distinguished Virginia family whose members played a prominent role in the political, military and cultural life of Virginia. Among the more famous of the Lees was Robert’s father, Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, a Revolutionary War general who distinguished himself for his military skills in numerous battles, culminating in the Battle of Yorktown in 1781 (he also was appointed by President Washington to lead an army to suppress the “Whiskey Rebellion” in 1794). Following in his father’s footsteps, Robert E. Lee was a star student at West Point. After graduating in 1829, he served with distinction as a military engineer and then as a soldier in the Mexican-American War (1846-48). Altogether, he served in the military for over three decades.

During the war, Lee experienced several setbacks in his personal life. Early on, Union troops confiscated his home at Arlington on the Potomac River, and he never got it back. Just before war broke out, his father-in-law passed away, leaving an estate in shambles, and Lee was forced to take leave from the army to tend to the plantation and its hundreds of slaves (whom he described as his “unpleasant legacy”). In 1862 he freed all of his father-in-law’s slaves. Historians disagree on whether Lee was a harsh master of those slaves before he freed them. Several accounts accuse him of brutal treatment of some of them, but whether he personally punished any slaves is still debated.

Today, we honor the memory of Robert E. Lee not for his battlefield exploits, or his positions on slavery, but for his leadership in bringing the Civil War to a peaceful end in April 1865, when he surrendered his armies to General Grant. After the war, Lee did not live long: he died this day on October 12, 1870 at the age of 63, while his former adversary General Grant was serving his first term as President of the United States. Lee’s wife outlived him by only three years. Lee is buried at the University Chapel of Washington and Lee University in Lexington Virginia, where he had been serving as President since the Fall of 1865. Originally known as “Washington University,” upon Lee’s death the university changed its name to Washington and Lee University. Lee’s son, George Washington Lee, followed his father as University President.