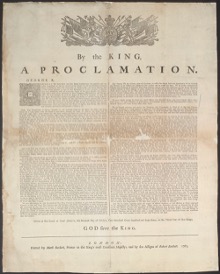

The “Royal Proclamation of 1763”

252 years ago on October 7, 1763, King George III of Great Britain issued a Royal Proclamation which laid out the new boundaries of the American colonies following the end of the French and Indian War. The war was concluded by the Treaty of Paris (not to be confused with the treaty of the same name that ended the American Revolution in 1783), and when peace was announced, American colonists breathed a sigh of relief—but only momentarily. For the King’s Proclamation, issued nine months after the peace treaty was reached, was immediately met with angry denunciations of the Crown’s line-drawing of the western boundary of the Great Britain’s North American colonies, which effectively barred Americans from moving west past the Appalachian mountains. Some historians point to this Royal decree as the first shoe dropping in what ultimately led to the commencement of the American rebellion ten years later.

The background of the King’s Proclamation is complex, but in simplified form, France had occupied the lands between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River, and shared that vast territory with various Native-American tribes. France also had established a presence in lands west of the Mississippi, which it also shared with Native-American tribes. Ignoring any claims of Native-Americans to ownership of those lands, in the 1763 Treaty of Paris France ceded all the lands east of the Mississippi and west of the Appalachian mountains to Great Britain, as part of a settlement of the broader Seven Year’s War in Europe, of which the war between France and Great Britain in North America was a part. As the new “owner” of those lands, the Crown decided that it should create an effective buffer against any further French incursions and Indian depredations by declaring all the lands west of the Appalachians to be “Indian Territory,” which would be off limits to British settlers.

Readers of this story should remember that in 1763, the “United States” did not exist—America was still a Crown Colony, and answerable to the Crown. American colonists were still British subjects, and beholden to the Crown for their overall welfare. In turn, however, the Crown wanted to encourage American colonists to expand the reach of the Crown’s presence in North America. Towards that end, King George III had bestowed generous land grants on various individuals and companies, most prominently American land companies formed by land speculators whose names we recognize today—most prominently, George Washington. Indeed, immediately following the end of the French & Indian War, Washington was given 20,000 acres of land in the Ohio region. With the issuance of the Royal Proclamation, those land grants—and the many settlements that already dotted the landscape west of the Appalachians– were imperiled. Any resolution of this problem, however, rested solely with the King, and the Proclamation made clear that no colonist or colonial authority had any right to occupy lands west of the Appalachians, or any right to acquire any such lands by way of purchase, treaty, or otherwise. Many colonists had fought and died to defeat the French, and to wrest control of the lands formerly occupied by the French in order to facilitate British expansion into the western frontier. Many colonists therefore viewed the Proclamation as a betrayal of the colonial cause, and as a reversal of long-standing Crown policy that granted significant rights to colonial governments to acquire lands, enter into treaties, and the like. Precedents for this extended back to the original settlers in New England who, in the 17th century, greatly extended the boundaries of the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies without necessarily seeking the permission of the King to do so. Now, an entirely new policy was being put into place—and the colonists didn’t like it.

What was King George III thinking? In significant part, he was seeking to delay what many observers thought was inevitable: the dispossession of Native Americans from tribal lands as American settlers moved west. By taking control of the lands acquired in the Treaty of Paris, the King hoped that western settlement could be undertaken in a more orderly fashion, while also calming the waters with some of the more hostile tribes. His concerns about potential violence were very real: Pontiac’s Rebellion had already broken out in 1763, and attacks were underway against various British forts on the western frontier. The Proclamation was intended to forestall further violence, which ultimately proved a fruitless exercise: colonists violated the terms of the Treaty of Paris with impunity, and proceeded to move west in contravention of the King’s line-drawing.

Looking back, the Proclamation appears to have been well-intentioned, but the King and his advisors seem to have not understood the depth of feeling of American colonists that North America was theirs for the taking. The general hostility of Americans towards the Proclamation was exacerbated by the Crown’s decision following the Treaty of Paris to keep a standing army in place to garrison forts and otherwise keep the peace. To many colonists, this posed the threat that British troops could be turned against them.

The Royal Proclamation precipitated the steady erosion of relations between Crown and Colony, and led to a decade of misjudgments and missed opportunities. As a concession to his colonial critics, in the period 1768 to 1770 the King signed off on several treaties with Native-Americans that further extended the western boundary of Great Britain’s colonies. These actions served to appease some colonists, but the perception that the Crown was violating their rights persisted. Those feelings intensified when the Stamp Act of 1765 was passed by Parliament (but repealed the following year after massive protests). The Stamp Act was yet another shoe dropping, followed quickly by the Declaratory Act of 1766. I may be accused of over-statement when I suggest that the Royal Proclamation of 1763 may have been the start of our American Revolution, but it is clear that it was the start of a rebellion against Crown rule, and set the American colonies on a path to war.

So today we commemorate the issuance of the Royal Proclamation of 1763– an event that profoundly affected the course of American history.