This year we commemorate the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It was signed in the midst of the American Revolution, which would not officially end until Great Britain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783. We know, of course, that the war between our two countries started in April 1775 with the battles of Lexington & Concord. But the causes of the war date back to February 1763, when Great Britain signed the first Treaty of Paris with its sworn enemy, France, against whom it had been fighting in North America for over a decade.

Scores of history books have been written, and hundreds of articles, attempting to explain the complex military and political machinations of what has to come to be known as the French & Indian War, so named because both sides in that war had recruited a number of Native-American tribes as their allies. French and British settlers had been active in areas of New England, the Great Lakes and the Ohio country for many years prior to the outbreak of war, and had developed strong trading relationships with a number of the tribes. Indeed, France had had a presence in North America since the earliest days of European settlement in North America, particularly in the area along the St. Lawrence River, Nova Scotia, and what is now northern Maine (or “Arcadia”). This area, called “New France,” became a bone of contention with Great Britain, which occupied the areas south of there, and viewed the French presence as an ongoing threat. As the British colonies expanded west, French settlers and many of the Native-American tribes likewise felt threatened. It was only a matter of time that things came to a head.

The first major battle that is often pointed to as the start of the French and Indian War took place on May 28, 1754: the Battle of Jumonville Glen in what is now western Pennsylvania. The British attack was led by none other than George Washington, a young Major in a Virginia regiment, who had been ordered to go west and help construct a fort in the Ohio country. Washington and his troops encountered a group of 40 French soldiers and attacked them, killing many of them, including their commanding officer. While neither France nor Great Britain officially declared war, for all intents and purposes the Battle of Jumonville Glen was the triggering event in the French and Indian War.

From 1754 to 1760, the warring armies engaged in multiple battles along the western frontier, with both sides sending troops from Europe to aid the cause. Many of the battles involved attacks on existing forts, such as Fort Oswego, Fort Niagara, and Crown Point. One of more famous battles was the Battle of the Monongahela, which took place east of present-day Pittsburgh Pennsylvania on July 9, 1755. In that battle, George Washington fought bravely, but his commanding officer, General William Braddock, was killed in action, along with 456 other British soldiers. It’s estimated that only 23 French soldiers were killed, and the battle was considered a massive defeat for the British forces. The French armies racked up several other victories in the period 1756-57, including the defeat of British forces in the Battle of Fort William Henry in August 1757, which was followed by the wholesale slaughter of captured British soldiers by the French army’s Indian allies. Despite these setbacks, the British army rallied in 1758, and achieved victory in several major battles, including the successful Siege of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia in 1758, the capture of Ticonderoga in 1759, and the successful Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec in September 1759.

Following this series of battles, a peace agreement of sorts was negotiated in September 1760, but the war was not officially ended until February 1763, when the Treaty of Paris was signed by Great Britain, France and Spain—part of a larger settlement between and among those countries that also resolved the European war referred to as the “Seven Years’ War.”

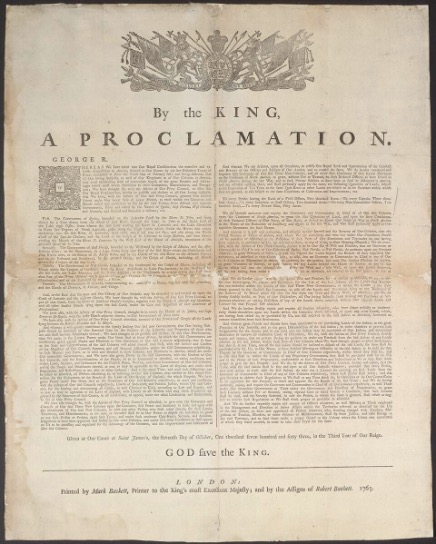

Many historians have argued that the 1763 Treaty of Paris was a major cause of the American Revolution. Why is that? The settlement terms included the surrender by France of its North American territories, which included the vast areas of French Canada it occupied, as well as its territories lying between the Mississippi River and the Appalachian Mountains. That was all well and good for Great Britain on paper, but the war had been incredibly costly—it had nearly doubled Great Britain’s debt, and now it was faced with occupying and defending the vast landholdings it had just acquired from France. This problem caused King George III to issue his Royal Proclamation of 1763, which was intended to set forth how all these new territories were to be governed. What set off the controversy between Great Britain and its existing North American colonies was a literal line drawing—the Proclamation drew a line from north to south along the crest of the Allegheny Mountains and announced that all the lands to the west of that line, all the way to the Mississippi, were now off limits to western expansion by the colonists. That area was to be preserved as “Indian Territory.” Further, colonists were barred from purchasing any of those lands from the Indians—only the Crown could approve and further acquisition of lands within the Indian Territory. One effect of this was to cancel many large land grants that had already been extended to various colonial land companies and private citizens, who of course were outraged by this “taking” of their lands. This became the first rallying cry among the colonists to oppose what was perceived as an act of oppression, which would only continue in the 1760’s with further impositions such as the Stamp Act of 1765, and the Townsend Acts of 1767. These and other legislative missteps led inexorably to the Tea Act of 1773, the Intolerable Acts of 1774, and—finally—the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775.

How did life change in the colonies in the immediate aftermath of the Royal Proclamation? At some levels, nothing changed: colonists often ignored the restriction on western expansion, and migrated into the prohibited areas regardless of the consequences. And for the most part there were no consequences, as Great Britain was not in a position to effectively police the vast territories into which the colonists were moving. One consequence, however, was that these territories were not just empty land—they were occupied by a number of Indian tribes, and they resisted the incursions of white settlers into their lands. This circumstance led to Pontiac’s Rebellion, which lasted from 1763 to 1766.To the extent the “Proclamation Line” was intended to protect the homelands of the tribes, once again Great Britain was largely powerless to stop the rising tide of western expansion.

It needs to be pointed out that the Royal Proclamation’s “line drawing” led to a series of legislative fixes, which were meant to reduce the tensions caused by the prohibition on western expansion. One example is the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, which adjusted the border between white America and the Iroquois Confederacy. But deep resentments continued, and the Proclamation left a lasting impression on the colonists that their government “back home” in England was not to be trusted. Indeed, many colonists concluded that their King & Parliament were more interested in protecting the Indians than supporting the economic growth of its thirteen colonies. Some Americans did quite well, notwithstanding the political turmoil: George Washington, for example, was given 20,000 acres of land in the Ohio Territory.

Yet for the average American, the Royal Proclamation was viewed as an overtly hostile act by a repressive absentee government, and in retrospect, it became a triggering event in our nation’s move towards independence.