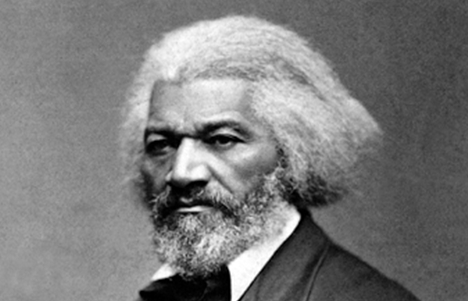

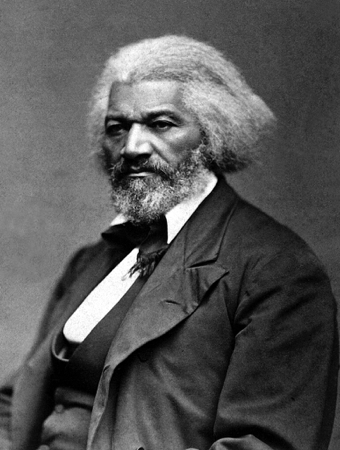

We have posted before about the Civil War era and Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. Much of the impetus for Lincoln’s Proclamation came from the radical abolitionists in the North, as well as African-American leaders. Perhaps the most famous of them was Frederick Douglass, who died this day on February 20, 1895 at the age of 77.

Douglass was himself a freed slave from Maryland, having escaped from his master in 1838. Douglass later wrote that his father was a white man, and some historians have suggested that his father was in fact his master. Largely self-taught, he began reading newspapers at age 12, and became highly literate at a young age. After fleeing to a safe house in New York City, Douglass became a vocal advocate against the institution of slavery, and made many speeches around the country in subsequent decades, including the years following the Civil War. He also wrote extensively, including three books: his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845); his second book, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855); and his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881). One of Douglass’ most famous speeches, still considered one of the greatest anti-slavery speech of all time, was “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?“, which he delivered in 1852.

By the end of the 1850’s, Douglass had formed alliances with some of the most hard-core radical abolitionists in America, including John Brown. In fact, Douglass had met with Brown right before Brown’s famous raid at Harper’s Ferry in 1859, which led to Brown’s trial and execution. Douglass later distanced himself from Brown, and said that he told Brown that his planned raid was suicidal. Whatever may have been said, Douglass was careful thereafter to avoid an outright endorsement of violence. Yet, during the Civil War, Douglass frequently pushed President Lincoln to abolish slavery, knowing that it was bound to lead to further violence and mayhem if Lincoln did so. Even after Lincoln finally issued his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Douglass urged Lincoln to grant voting rights to freed black men. Lincoln stopped short of that, and as a result Douglass ended up supporting Lincoln’s rival, John C. Fremont, a strong supporter of black male suffrage, in the Presidential election of 1864. Long after the Civil War ended, and Lincoln had been assassinated, Douglass pejoratively described Lincoln as “the white man’s president.” Douglass continued to relentlessly pursue the cause of freedom for freed blacks for the next several decades, right up to his death in 1895.

As for Douglass’ personal life, while still a slave he met and fell in love with an older African-American woman, Anna Murray. It was Anna who may have inspired Douglass to escape. They were married just a few days after Douglass arrived in New York. They subsequently moved to Massachusetts, and later to Rochester New York. They raised five children. Some historians have written that while the marriage was a good one, Douglass may have been unfaithful; his relationship with Ottilie Assing, a much younger white woman, was the subject of rumors for many years. After Anna died in 1882, Douglass married another white woman, Helen Pitts. Upon hearing the news, Ottilie committed suicide.

Douglass died of a heart attack after giving a speech in Washington D.C. His death triggered a massive outpouring of grief. He was buried at the Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York, next to his first wife Anna. When his second wife Helen died in 1903, she too was buried there. His grave marker describes him as an “escaped slave, abolitionist, suffragist, journalist and statesman, founder of the Civil Rights Movement in America.”

And so today, on the 130th anniversary of his death, we honor the memory of Frederick Douglass, a true champion of civil rights and racial equality.