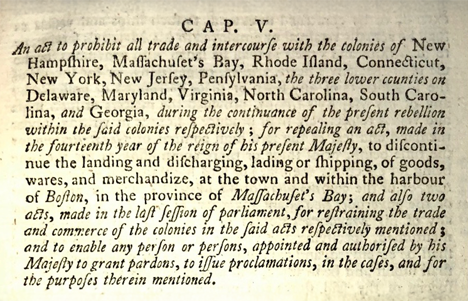

While it was only one paragraph long, the Prohibitory Act of 1775 was a bombshell for the American colonists who were now at war with their mother country, Great Britain. In the Fall of 1775, Americans were still British citizens, and still owed their allegiance to King George III—at least in theory. The war, begun in April with the “shot heard round the world,” was now in full swing. The Americans had chalked up a few victories and inflicted heavy losses on British troops (the Battle of Bunker Hill in particular). By the Fall, the war-hawks in the British Parliament concluded that something else was needed to end the war than just fighting it out with muskets and bayonets.

That something else was the Prohibitory Act. With a stroke of the pen, Parliament declared that England was going to cut off all trade with its American colonies—a disastrous blow to American merchants—institute a blockade of American ports, and authorize the seizure of American ships at sea. Clearly the intent was to damage the American economy, and inflict pain and suffering on innocent civilians everywhere. While the Declaration of Independence was still a gleam in the eye of the 2nd Continental Congress, the Prohibitory Act left no doubt in the minds of many members of Congress: England was declaring war on its American colonies.

King George III signed the Act on December 22, 1775, making it official on that day 250 years ago. Parliament had passed the bill in late October, and for almost two months England had been ramping up enforcement of the Act while awaiting the King’s signature. For its part, during this interim period the 2nd Continental Congress authorized “privateering” —the equivalent of piracy—against British ships (at that point, America had no navy to speak of). This move no doubt was in retaliation for the seizures of American ships that were already taking place. Indeed, at a meeting of the Congress on November 25, a sense of outrage prevailed:

“… many vessels which had cleared at the respective custom houses in these colonies, agreeable to the regulations established by acts of the British parliament, have in a lawless manner, without even the semblance of just authority, been seized by his majesty’s ships of war, and carried into the harbor of Boston and other ports, where they have been riffled of their cargoes, by orders of his majesty’s naval and military officers, there commanding, without the said vessels have been proceeded against by any form of trial, and without the charge of having offended against any law.”

At that same meeting on November 25, Congress also expressed shock that British naval ships “have already burned and destroyed the flourishing and populous town of Falmouth, and have fired upon and much injured several other towns within the United Colonies…” The mayhem of war was accelerating at a rapid pace.

The Prohibitory of 1775 Act disabused many colonists from thinking that there might be a peaceful outcome of the war effort, and no doubt caused them to question their allegiance to the King—or to outright abandon any such allegiance. If political leaders in England thought the Prohibitory Act would turn the tide of war, they were badly mistaken.