Months after the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” kicked off the American Revolution in April 1775, a large number of colonists—a very large number– were still reluctant to declare independence from Great Britain, or to renounce their allegiance to the King of England, George III. Among those still hoping for reconciliation were a few leading members of the 2nd Continental Congress. From the perspective of General Washington and his troops, America was holding its own in the war, and at the end of 1775 the Continental Army was besieging British troops in Boston (and ultimately forced the evacuation of Boston the following year). Yet, the American forces were colossally outnumbered by the number of British “regulars” still in the colonies, and the Continental Army was under-resourced: not enough food, clothing or ammunition to properly conduct warfare. The 2nd Continental Congress knew this, and knew that the likelihood of victory over British forces was uncertain at best.

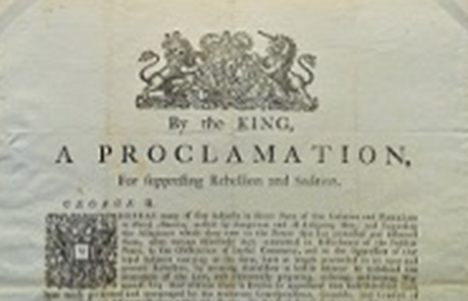

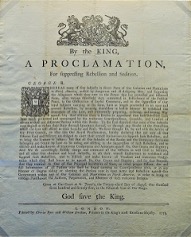

In the summer of 1775, a major political mis-step took place that may have sealed the fate of Great Britain. Having just “won” the Battle of Bunker Hill in June, the British Army was reeling from the tremendous number of soldiers who were killed or wounded in the battle (as well as in the Battle of Lexington & Concord in April), a fact that led many political observers to conclude that unless peace could be restored, the war would be a long and painful one. King George III, however, concluded that any efforts at reconciliation must be shelved, and the war prosecuted with even greater vigor. Thus, on August 23, he issued a Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition, taking aim at the leaders of the rebellion, and declaring that these “dangerous and ill designing men” were now in “open and avowed rebellion,” and were “traitorously preparing, ordering and levying war against us.” His loyal subjects in America must now “bring the traitors to justice,” and “disclose and make known all treasons and traitorous conspiracies which they shall know to be against us.” The King reminded them of the “allegiance which they owe to the power that has protected and supported them,” and urged them that if they act accordingly, they will enjoy the “protection which the law will afford to their loyalty and zeal.”

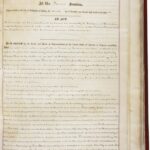

Because of the length of time it took for written communications to travel across the Atlantic, the King’s Proclamation did not reach the shores of America until sometime in September or October (historians have long debated exactly when it arrived). When it was read, the members of the 2nd Continental Congress were stunned—or at least some of them were. The Congress concluded that it must respond, and that it must refute the charges the King had leveled against the colonists. It therefore appointed a Committee on Proclamations to review the King’s August 23 Proclamation, and report back. On December 6, 1775, the Congress released the Committee’s report. A far longer document than the King’s Proclamation itself, the Report began with a declaration that the Congress intended to “wipe off… the aspersions which [the King’s Proclamation] is calculated to throw upon our cause; and to prevent, as far as possible, the undeserved punishments, which it is designed to prepare, for our friends.” No doubt, in writing this, members of Congress were aware that if any of them or their friends were found to have committed treason, the penalty under British law was death. The December 6 Report was an ultimately failed attempt to persuade the Crown that the American colonists were acting in good faith—and that they certainly were not traitors.

Overall, the Report may have done more harm than good. In response to the charge of disloyalty, the Report asked “what allegiance is it that we forget? Allegiance to our King? Our words have ever avowed it [and] our conduct has ever been consistent with it.” We are loyal subjects, the Report insisted, arguing that all they were guilty of was “opposing the claim and exercise of unconstitutional powers, to which neither the Crown nor Parliament were ever entitled.” In that same vein, the Report contended that “we have resisted [the Crown] only in those cases in which the right to resist is stipulated is expressly on our part, as the right to govern is, on other cases, stipulated on the part of the Crown.” As one example, “the cruel and illegal attacks, which we oppose, have no foundation in the royal authority.” The Report was unyielding in its stance that the colonists had never acted other than justifiably, and that the Crown and Parliament had consistently violated British law.

The December 6 Report at times mocked the King, and at other times chastised him. “Rebellion is a term undefined and unknown in the law,” the Report quarreled, arguing that a “Proclamation” was not a proper exercise of royal authority unless it was “merely enforcing what is already law.” The Report asked, “can Proclamations, according to the principles of reason and justice, and the Constitution, go farther than the law”? If the intent of the Report was to assuage the King’s fears that the American colonies were in open revolt, this kind of rhetoric was counter-productive, to say the least.

It’s also fair to say that the Report was disingenuous. In particular it failed to acknowledge that the Colonies were, as a practical matter, in “open rebellion,” even if they had not yet declared independence. How else to characterize the Congress’ decision to create a Continental Army (which it did in June 1775), appoint George Washington its Commander in Chief, order the raising of troops to support the cause, and authorize the purchase of 500 tons of gunpowder (which it did in September)? Whatever the case, the Report’s aggressive tone did little to conciliate matters, and perhaps was never intended to do so. Indeed, at the time the Report was written, the British Navy just weeks before had burned the coastal port of Falmouth, Massachusetts (today’s Portland, Maine), after the captain of the British ship HMS Canceaux sent ashore a proclamation that he was there to “execute a punishment” for the townspeople’s support of the rebellion. The Burning of Falmouth cemented Congress’ determination to oppose British forces with all the troops and supplies it could muster.

The Report then delivered a not-so-veiled threat: if, under the terms of the King’s Proclamation, “any persons in the power of our enemies” were punished for allegedly supporting the rebellion, such an action “shall be retaliated in the same kind, and the same degree upon those in our power, who have favored, aided, or abetted, or shall favor, aid or abet the system of ministerial oppression.” Note the use of the word “enemies,” which was directed, quite clearly, at the Crown and Parliament. How could King George III not view these words as traitorous?

The final paragraph of the Report sounded a note of resignation. Great Britain and the Americans were now in the midst of an “unhappy and unnatural controversy, in which Britons fight against Britons.” War was raging, the Report acknowledged, and death and destruction was inevitable. Seeing no end in sight, “let the calamities immediately incident to a civil war suffice. We hope additions will not from wantonness be made to them on one side. We shall regret the necessity, if laid under the necessity, of making them on the other.” The meaning was unmistakable: if the British began to punish civilians accused of supporting the rebellion, the Americans would make “additions” to the “calamities immediately incident to a civil war” as well. Fighting words, indeed.

The full text of the December 6 Committee on Proclamations’ Report can be found in the Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774- 1789, vol. III (pp. 409-412) (available for free download on archive.org).

Before the December 6, 1775 Report had even made its way to England and been read by the King, the next shoe had already dropped. On December 22, 1775, Parliament enacted the Prohibitory Act, pursuant to which the British government cut off all trade with the American colonies, instituted a blockade of American ports, and authorized British vessels to seize American ships and take the ships’ crews. The war had been raging for a year and a half. Clearly Parliament had had enough, and believed that economic sanctions of this sort would weaken the American war effort substantially.

As we now know, the Prohibitory Act was one of several actions the Crown and Parliament took in 1775 and the first half of 1776 that only increased American colonists’ support for independence, which finally came in July 1776 with the signing of the Declaration of Independence. In December 1775, many colonists were still “on the fence.” But the substance and tone of the Prohibitory Act caused them to rethink, especially those colonists whose livelihoods depended on trade (merchants, planters, artisans and craftsmen, and all manner of other citizens). Painting with a broad brush, Parliament accused “many persons” in the thirteen colonies to “have set themselves in open rebellion and defiance to the just and legal authority of the King and Parliament,” and American political leaders had “usurped the powers of government” from the Crown and Parliament. Great Britain must act, therefore, to “suppress such Wicked and daring designs,” and put an end to “said rebellious and treasonable commotions.” Fighting words, again.

Looking back, the war of words between the British government and the 2nd Continental Congress in December 1775 was a harbinger of things to come. Had saner heads prevailed, perhaps the King would not have delivered his Proclamation, and instead would have looked for a peaceful resolution of the war. It was another missed opportunity, and his Proclamation surely persuaded many members of Congress that the war must be won at all costs.