We’ve written a number of stories about the slow and steady erosion of Native-American tribal lands in the 19th century due to the encroachments of white settlers—the natural consequence of American government policies encouraging and enabling western expansion in the name of “Manifest Destiny.” One major piece of legislation that led to massive dislocation of Native-Americans was the Dawes Act of 1877, which was passed by Congress on this day in 1887.

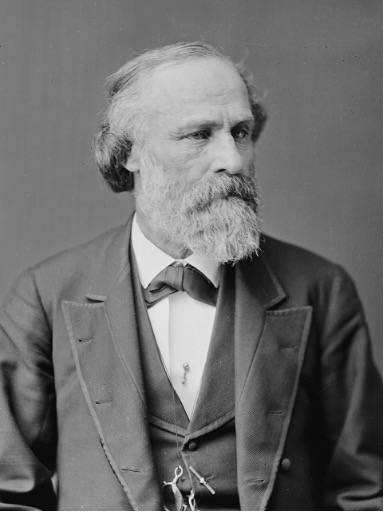

The Dawes Act was named for Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, who had served in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate for several decades, and was not by any stretch known to be a strident Indian-hater. On the contrary, he had been an anti-slavery advocate during the Civil War, and in the Senate, he chaired the Committee on Indian Affairs. He was, if anything, a well-meaning proponent of doing something to “save” the Indians.

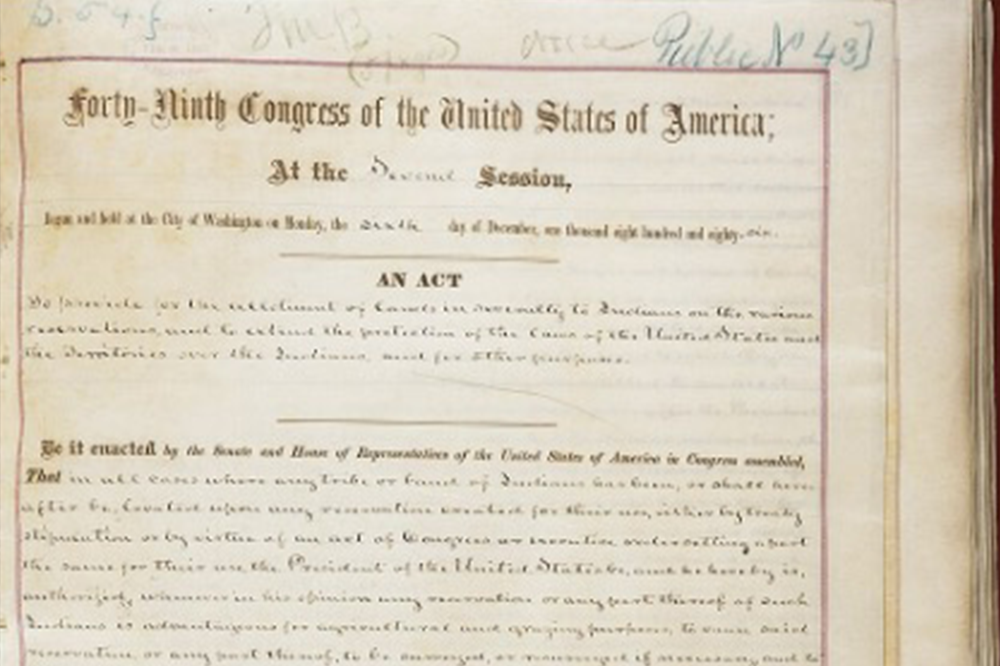

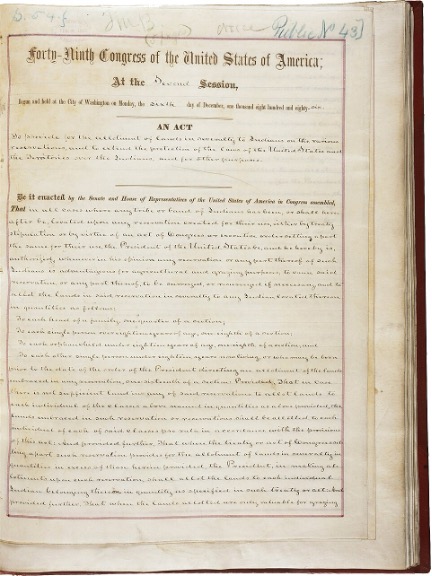

The long title of Dawes’ bill sets forth the basic purpose of the statute: “An Act to provide for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations…” What the law translated into was a dismantling of the reservation system over time, by mandating the transfer of reservation lands to Native-Americans individually, a process that served to reduce the size of reservations dramatically, and also allow for the subsequent transfer of lands allocated to individual Native-Americans into the hands of non-Native Americans.

Most assuredly, the Dawes Act and the legislative debates surrounding its passage were couched in benign terms, affirming that Congress’ intent was “to extend the protection of the laws of the United States and Territories over the Indians,” to encourage Native-Americans to “assume a capitalist and proprietary relationship with property,” and to promote Native-Americans’ “absorption into the American mainstream.” None of this, of course, was what Native-American tribes had been seeking, nor were these purposes compatible with Native-American culture, which emphasized concepts of communal living and sharing. The paternalist tone of the legislative debates masked what the law really was intended to accomplish: a veritable land grab at a time when some of the western tribes were on the brink of extinction following a series of battles such as the Dakota War of 1862, the Modoc War of 1872-73, the Nez Perce War of 1877, and the Great Sioux War of 1876-77 (even after the Dawes Act was passed, these wars continued, culminating in the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890).

Underlying all of this were two themes that had taken root in American minds decades previously, fueled in part by the concept of “Manifest Destiny.” The first theme was simple: Native-Americans needed to give up their way of life—hunting over vast open rangelands—and settle down to agrarian lives of subsistence farming and ranching, just like white settlers did. The second theme was a religious one: Native-Americans needed to convert to a Christian life, and their children should be taught in Christian schools. By the 1880’s, American political and military leaders had concluded that the assimilation of Native-Americans into American culture was not only desirable, it was inevitable. Many Native-Americans already had come to the same conclusion, and had started down the path of assimilation. But the Dawes Act represented a gigantic shove to Native Americans to get with the program. By pushing Native-Americans into a life of private land ownership, the sponsors of the Dawes Act thought that Native-Americans would rapidly adopt an American way of life and take responsibility for their own care and feeding, without the support of the reservation system.

What exactly did the Dawes Act promise Native-Americans in exchange for giving up their tribal way of life? Each head of household would receive 160 acres, or a single person 80 acres; the land allotments would be held in trust for 25 years (that is, the recipients would not actually own their land for 25 years!); and the recipients of the grants had four years to select their land, or the Secretary of the Interior would select it for them. There were duties and responsibilities that went with these land grants: all recipients would be subject to the laws of the state or territory in which the person resided, pay taxes, and otherwise be subject to the same rules as white people. The carrot and stick, if you will, is in return, recipients of the land grants would be granted U.S. citizenship.

Starting in 1887, the wheels were set in motion to implement the provisions of the Dawes Act. A “Dawes Commission” was created, with a mission of convincing as many tribes as possible to participate openly and willingly in the process of assimilation. Dawes himself served on the Commission for ten years. Indians who agreed to receive allotments of land were placed on the “Dawes Rolls.” The end result of this process was predictable: it is estimated that the original tribal lands left unallocated exceeded 90 million acres, all of which reverted to the U.S. government. This represented about two-thirds of the reservation lands in existence when the Dawes Act was passed in 1887. Hunting became an obsolete means of subsistence, and tens of thousands of Native-Americans were displaced.

So today, we pause to consider how the Native-American way of life might have evolved had the Dawes Act not become law; how tribal lands might have been preserved; and how western migration might have proceeded without the wholesale displacement of Native-Americans in the West. Was displacement inevitable? Given the politics of “Manifest Destiny,” the answer seems to be yes.