On January 16, 1786, the State of Virginia enacted a ground-breaking piece of legislation known as the Act for Establishing Religious Freedom. The Virginia statute is noteworthy for the man who authored it: Thomas Jefferson. Reflecting its importance to Jefferson, his “Act for Establishing Religious Freedom” was one of only three accomplishments he had engraved on his tombstone:

“Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, and father of the University of Virginia.”

The history of the statute is a tortured one. Jefferson actually drafted the text way back in 1777, while the American Revolution was still raging, and Jefferson was serving as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates. It took two years for the proposed statute to be introduced in Virginia’s General Assembly in 1779, and proceeded to be ignored, presumably because the Virginia legislature was focused on supporting the war effort. The war continued to rage until the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, followed by the Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783.

Once peace broke out, political leaders in Virginia returned to their role as lawmakers. One subject that rose to the surface almost immediately was whether and how to support public education of the state’s youth, since the war years had taken its toll on education while Virginia was experiencing battle after battle within its borders. In the past, many of the colonies had enacted various statutes that placed restrictions on the liberties of citizens who didn’t subscribe to the Christian faith. These faith-based proscriptions dated back to the very founding of the country, the strict Puritan rule of law in the Massachusetts Bay Colony being one example. Virginia was no exception: it was founded in 1607 when the first English settlers arrived at Jamestown and established a colony that strictly adhered to the theology of the Church of England. Religious tests for who could vote persisted, including laws restricting voting rights to only those persons who were members of the local congregation. And so on.

One would think that the principles of the English “Enlightenment,” which heavily influenced the thinking of our Founding Fathers about the freedoms and liberties over which the American Revolution was being fought, would have resulted in a strong public policy throughout the new United States supporting religious freedom after the war was concluded in 1783. Not so: religious biases of one sort or another continued, including in the State of Virginia.

The triggering event leading to the passage of the Act for Establishing Religious Freedom was a bill introduced in the General Assembly just four months after the conclusion of the war. On January 1, 1784— New Year’s Day! — none other than Patrick Henry of “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” fame introduced legislation entitled “A Bill Establishing a Provision for Teachers of the Christian Religion.” The bill was remarkable in its matter-of-fact assumption that the people of Virginia were willing to be taxed “for the support of Christian teachers,” and for no other purpose. Patrick Henry’s bill was careful to assure Virginia’s citizens that his law was not intended to “counteract the liberal principle heretofore adopted and intended to be preserved by abolishing all distinctions of preeminence amongst the different societies or communities of Christians” — but to the modern eye, that’s what his legislation did, at least as respects supporting teachers: only Christian teachers need apply.[1]

Virginia political leaders reacted quickly to Patrick Henry’s proposed legislation. One of the most vocal opponents was future President James Madison, who in 1784 was in between jobs, but was soon to lead the effort of drafting and passing our U.S. Constitution. While Patrick Henry’s bill was pending, in June 1785 Madison published a tract entitled “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments.” The tract was long-winded, but said in so many words that Patrick Henry’s bill, “if finally armed with the sanctions of law, will be a dangerous abuse of power.” Madison emphasized that the practice of any religious belief “can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence.” More colorfully, he said that “the Rulers who are guilty of such an encroachment… are Tyrants.” Madison saw the larger threat that Patrick Henry’s bill posed:

“Who does not see that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other Religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other sects? That the same authority which can force a citizen to contribute three pence only of his property for the support of any one establishment, may force him to conform to any other establishment in all cases whatsoever?”

Madison expounded eloquently and relentlessly in his “Remonstrance” against the proposed legislation, setting forth in fifteen separate paragraphs his specific criticisms. He summed it all up in his final paragraph, in which he wrote that just as the Virginia legislature could not control the freedom of the press, nor abolish the trial by jury, the Virginia legislature had “no authority to enact into law the Bill under consideration.”

Madison’s “Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments” had the intended effect. Jefferson’s bill, which had languished for years, was re-introduced, and Madison led the effort to see it enacted, which was successfully done on January 16, 1786.

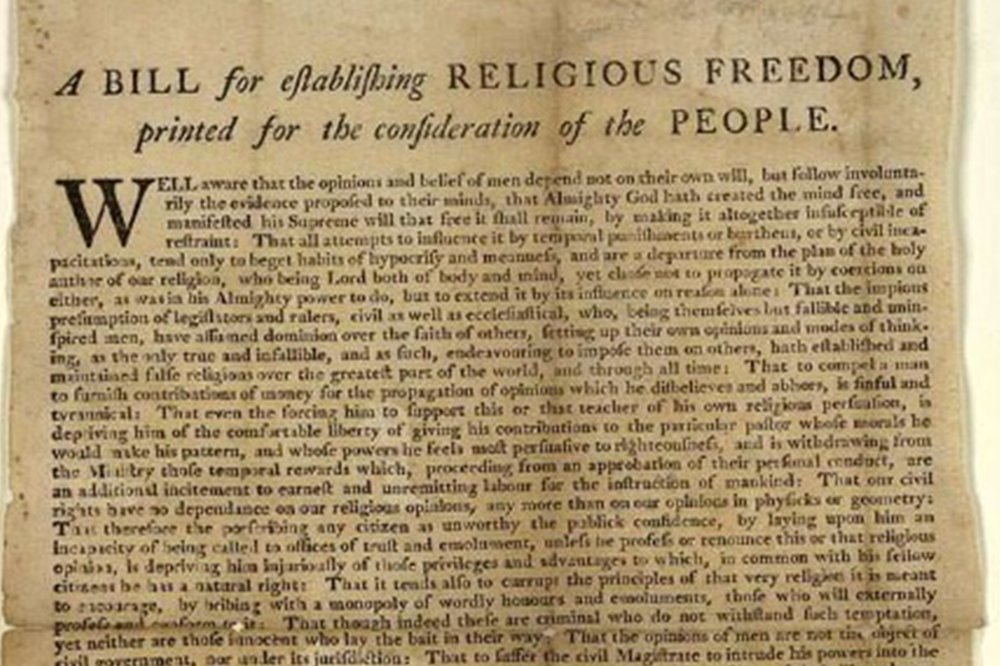

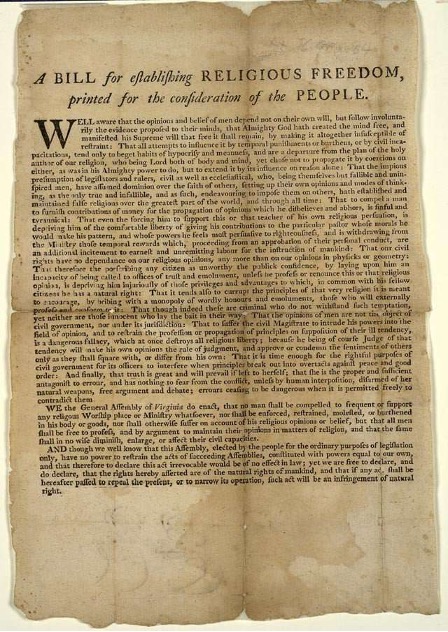

What did Jefferson’s Act for Establishing Religious Freedom actually say or do? His bill was straightforward, starting with the preamble to the text of the legislation itself: he entitled it “an act of establishing religious freedom.” Like his Declaration of Independence, in which he excoriated King George and Parliament for their various oppressions of the American people, Jefferson’s Act for Establishing Religious Freedom blasted the clergy, “being themselves but fallible and uninspired men [who] have assumed dominion over the faith of others,” and who “have established and maintained false religions over the greatest part of the world.” Jefferson also attacked the practices in the United States of barring men from office “unless he profess or renounce this or that religious opinion,” and of the “civil magistrate [who] intrudes his powers into the field of opinion… which at once destroys religious liberty.”

The final paragraph of Jefferson’s Act for Establishing Religious Freedom sets forth the actual law that was to be enacted, and is a clarion call for religious freedom:

“Be it enacted by the General Assembly that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief, but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of Religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge or affect their civil capacities.”

Virginia’s Act for Establishing Religious Freedom was soon to serve as one of the templates for our Bill of Rights, which in the First Amendment bars the government from establishing an official religion, or from favoring one religion over another. It was the Virginia law, well known to James Madison, that no doubt helped shaped the thinking of our Founding Fathers in their deliberations over the Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

So on this day, we give thanks to Thomas Jefferson, whose enlightened thinking led to passage of one of the first official declarations of religious liberty in United States history.

[1] The implementation of Henry’s proposed tax left taxpayers no choice but to pay money towards a decidedly Christian cause. A Sheriff would collect the tax, which the taxpayer could designate towards a specific church, or no church at all. Lists would be kept and made publicly available showing who paid, and for what purpose. A person who chose not to designate his tax payment to a specific church would see his money “disposed of… for the encouragement of seminaries of learning within the Counties whence such sums shall arise, and for no other use or purpose whatsoever.”