How the Jay Treaty of 1794 Unleashed a National Debate Over American Trade and Commerce with Its Former Foe, Great Britain.

In the decades following the end of the American Revolution in 1783, our nation’s political leaders grappled with a wide array of domestic and international issues that would define just what kind of constitutional republic we would be, now that America was a truly independent nation able to shape its own destiny. A main concern was America’s foreign relations with Great Britain, and specifically the concern that the British were not honoring the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris, and was refusing to withdraw its forces from forts in the Northwest Territory that now belonged to the new United States. An equal if not greater concern was America’s rights—or lack thereof—to navigate the Mississippi River, which was a principal means for America’s western states and territories to engage in trade and commerce with the rest of the world. Relatedly, the British Royal Navy had begun seizing American ships at sea, confiscating goods and capturing American sailors. Finally, not to be overlooked, it was believed that the British were arming hostile Native-American tribes that were resisting America’s efforts to settle the Northwest Territory. All of this had led the U.S. government sought a trade embargo on British goods in March 1794, but the motion was defeated in the U.S. Senate. It was clear to all that new agreements between Great Britain and the United States were needed to resolve these and other critical issues.

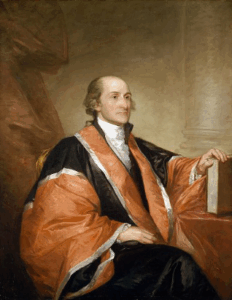

Enter John Jay. A largely forgotten man today, in his time Jay was one of the most important political figures in the country. In the years leading up to the ratification of our Constitution, Jay was a Founding Father, President of the Continental Congress, Minister to Spain, and Secretary of Foreign Affairs. Most notably, Jay was one of the primary negotiators with Great Britain over the terms of the Treaty of Paris which officially ended the Revolutionary War in 1783. As a testament to Jay’s critical role during the war years, John Adams said that Jay was “of more importance [to the treaty negotiations] than any of the rest of us.” Later, Jay served as Secretary of State under George Washington (1789-1790), and was then appointed by Washington to serve as the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (1789-1795). Jay was an avowed Federalist (a co-author of the Federalist Papers), and for that he was the target of the emerging opposition party of anti-federalists who resisted “big government,” but who strongly advocated free trade and western expansion.

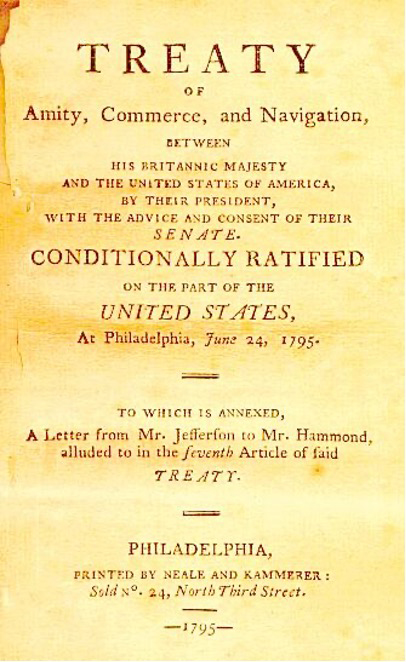

In 1794, in the midst of his tenure as Chief Justice, Jay was given an out-of-the-blue assignment by President Washington: he was to become a special envoy to Great Britain, and he was to immediately travel to England to negotiate a new treaty, which came to be called “The Jay Treaty.” With instructions drafted by Secretary of State Alexander Hamilton in hand, Jay went to work, and he worked quickly– perhaps too quickly, in some people’s minds. On November 19, 1794, the United States and Great Britain signed the “Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America.” The treaty was, however, subject to ratification by the U.S. Congress.

What was the Jay Treaty, and why did it trigger a political crisis back home? To the treaty’s negotiators and members of Washington’s administration, the treaty was viewed as a “win.” The key terms of the treaty were straightforward:

- Great Britain agreed to vacate its forts in the Northwest Territory by June 1796;

- Americans were given “most favored nation” status in trading with Great Britain

- American, British and Native American peoples were given free passage across each other’s respective countries or territories, “by land or inland navigation;”

- Americans were granted restricted commercial access to trade in the British West Indies;

- Commissions would be established to set definitive boundaries in the Northeast and Northwest.

Pursuant to these various agreements, Great Britain paid over $11 million for damages to U.S. shipping, and the U.S. paid Great Britain 600,000 British pounds for unpaid pre-War debts.

Left unresolved were a few issues that were important to many Americans. First, there was no resolution of Great Britain’s maritime practices against U.S. ships at sea (an issue that would ultimately trigger the War of 1812). Second, there was no resolution of the Southern slaveholders’ demands for compensation for the value of slaves that has escaped to the British forces during the Revolution, which further enflamed the anti-Federalists, many of whom were Southern slaveholders.

The Senate first took it up the treaty in June 1795, with a two-thirds majority vote required to approve the treaty. The treaty’s terms were almost immediately attacked by leading anti-federalists, who were allied with then-Vice President Thomas Jefferson (and later, James Madison). The politics of the Jay Treaty were bound to cause vigorous debate, and the opposition quickly became quite personal, with many public attacks being launched against Jay himself: “Damn John Jay!” became a rallying cry at town hall meetings and public rallies around the country.

Ultimately, the Jay Treaty was ratified by the Senate by a vote of 20-10, and President Washington signed it into law in August 1795. But the legislation now needed to receive funding from the House of Representatives, or the terms of the treaty could not be fulfilled. After long and acrimonious debate, the House finally approved the funding by a vote of 51 to 48 on April 29, 1796.

Ultimately, the Jay Treaty was ratified by the Senate by a vote of 20-10, and President Washington signed it into law in August 1795. But the legislation now needed to receive funding from the House of Representatives, or the terms of the treaty could not be fulfilled. After long and acrimonious debate, the House finally approved the funding by a vote of 51 to 48 on April 29, 1796.

The acrimony generated by the Jay Treaty did not dissipate following its ratification. Indeed, what emerged from the debates over the Jay Treaty was never anticipated by the Founders: an emergent two-party system, in this case the Federalists vs. the “Democratic-Republican Party” led by Jefferson. This paradigm shift in American politics would manifest itself most prominently in the election of 1800, in which Thomas Jefferson defeated John Adams’ bid for reelection, and the era of “Jeffersonian Democracy” began. Ironically, when Jefferson became President, he did not kill the treaty, and it remained in effect until it expired on its own terms in 1805. Efforts to renew the treaty failed.

Looking back, modern historians are of two minds about whether the Jay Treaty was, in fact, a “win.” Prize-winning historian Joseph Ellis concludes that the treaty was a “one-sided” win for Great Britain, while historian Bradford Perkins saw it as a temporary win for America, in that it guaranteed many years of peace on America’s Western frontier, and vastly improved trade relations with Great Britain (before that all collapsed when war once again broke out in 1812). Most historians credit Jay with having brokered a treaty that was probably the best that could have been achieved under all the circumstances that existed in 1794.

As for Jay, his career in the federal government effectively ceased with the passage of the Jay Treaty. He resigned as Chief Justice in June 1795, and immediately took up the Governorship of the State of New York, a position he held until 1801. He did not necessarily divorce himself from national politics, however: he sought the U.S. presidential nomination in 1796 and 1800, but he received almost no support. In 1801 he declined another term as Governor of New York, and chose to leave politics entirely.

John Jay lived a long life after politics, passing away in May 1829 from cerebral palsy. He was the very last surviving President of the Continental Congress, and the last surviving delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774. One can reasonably say that John Jay had “seen it all.” And so today we commemorate the anniversary of one of John Jay’s greatest achievements: the successful negotiation of the treaty that bears his name, the Jay Treaty, which was signed on this day on November 19, 1794.