Long forgotten today, one of the most important political figures in 17th century colonial America was William Berkeley, who died this day on July 9, 1677. Berkeley was the Governor of the Virginia Colony from 1642 to 1652, then again from 1660 to 1677. During the better part of four decades, Berkeley accomplished many good things as Governor, but over time he lost the confidence of his people, culminating in Bacon’s Rebellion, considered by many historians to be America’s first revolution. Berkeley’s tenure as Governor took place during one of the most challenging eras to be faced by any Governor of the Virginia Colony: besides ongoing violence with native-American tribes, the rebellion led by Nathaniel Bacon in 1676 forced Berkeley to take up arms against his own people in order to restore order. Admittedly, Berkeley took many extreme positions, including opposing public education of his people, which he said would bring “disobedience, heresy and sects to the world.” Ultimately, Berkeley was forced to step down, and he returned to England shortly about the Rebellion was quelled.

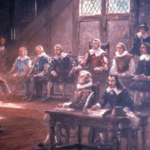

Bacon’s Rebellion was Berkeley’s worst nightmare, but what triggered it? There were many reasons, most notably the steady increase in Indian attacks that destroyed lives and property, in response to which Berkeley did little to fight back against the Indian “hostiles,” or to otherwise strengthen the Colony’s defenses. Nathaniel Bacon emerged as a leading voice for those colonists who were fed up, and who wanted to fight back. Against Berkeley’s orders, in 1675 Bacon led a group of colonists against Powhatan warriors in retaliation for their most recent series of attacks designed to “in all places burn, spoil and murder.” Berkeley’s view was that the colonists should try to make peace with their Indian neighbors, but that strategy was failing badly. Nevertheless, he could not tolerate Bacon’s insurrection, and declared him a rebel. Since Bacon was also a member of the Virginia General Assembly at the time, Berkeley decided to dissolved the General Assembly, and took the government under his personal rule.

The Rebellion was not just about Berkeley’s failure to deal wit4h the “Indian problem. In fact, the rebellion soon evolved into a plebiscite on Governor Berkeley’s overall leadership: his administration was accused of widespread corruption, and Berkeley himself was attacked for imposing unjust taxes on the colonists. As the confrontation between Bacon and Berkeley escalated, Bacon issued a Declaration of the People of Virginia, a scathing indictment of Berkeley’s rule. In a few short paragraphs, Bacon laid out eight key complaints which in their totality attributed the collapse of democratic governance in the Colony to Berkeley’s willful failure to adhere to the principles of governance by the consent of the people. Bear in mind, this was a hundred years before our American Declaration of Independence! With utter bravado, Bacon proclaimed that Berkeley “has traitorously attempted, violates, and injures his Majesty’s interest hereby by a great loss of his colony and many of his faithful loyal subjects.”

It was indeed true that by that time, colonists were leaving Jametowne for greener pastures, including areas of what became Maryland and North Carolina—beyond the reach of Berkeley’s allegedly corrupt regime. Bacon’s manifesto was a call to arms, and the colonists rallied to his side. In 1676, Bacon and his men marched into Jametowne and burned it to the ground. With the momentum seemingly with Bacon and his men, suddenly the rebellion ended, when Bacon died of natural causes in October 1676. Although Berkeley therefore prevailed, the English government, lost faith in him, and Berkeley was recalled to London with a significant loss of reputation. After a new government was installed, the Virginia Colony slowly recovered.

As for Berkeley’s personal life, Berkeley had come from a wealthy English family, and received a first-rate education at Oxford. While still in his 20’s, Berkeley was appointed to work in the household of King Charles I. He later served with distinction in the royal army, for which he was knighted by the King. In 1670, during his second term as Governor, Berkeley married Frances Culpeper, the daughter of Thomas Culpeper, one of the prominent investors in the Virginia Company. William and Frances lived together at the Green Spring Plantation, said to be one of the finest houses in all of 17th century Virginia. Upon William’s death on July 9, 1677, Frances became one of the wealthiest—if not the wealthiest—of all Virginia colonists. The Culpeper family prospered in Virginia, and Frances’ cousin, Thomas Culpeper, became Governor of the Colony in July 1677, the same month in which Berkeley died. Berkeley was buried in a crypt at St. Mary’s Church, Twickenham. Today, visitors can see a memorial window in the church, in his honor.

So today, we honor the memory of William Berkeley, an important figure in American history, who served his country as best he could at a time of great challenges in the Virginia Colony.