Background and Prelude to Battle

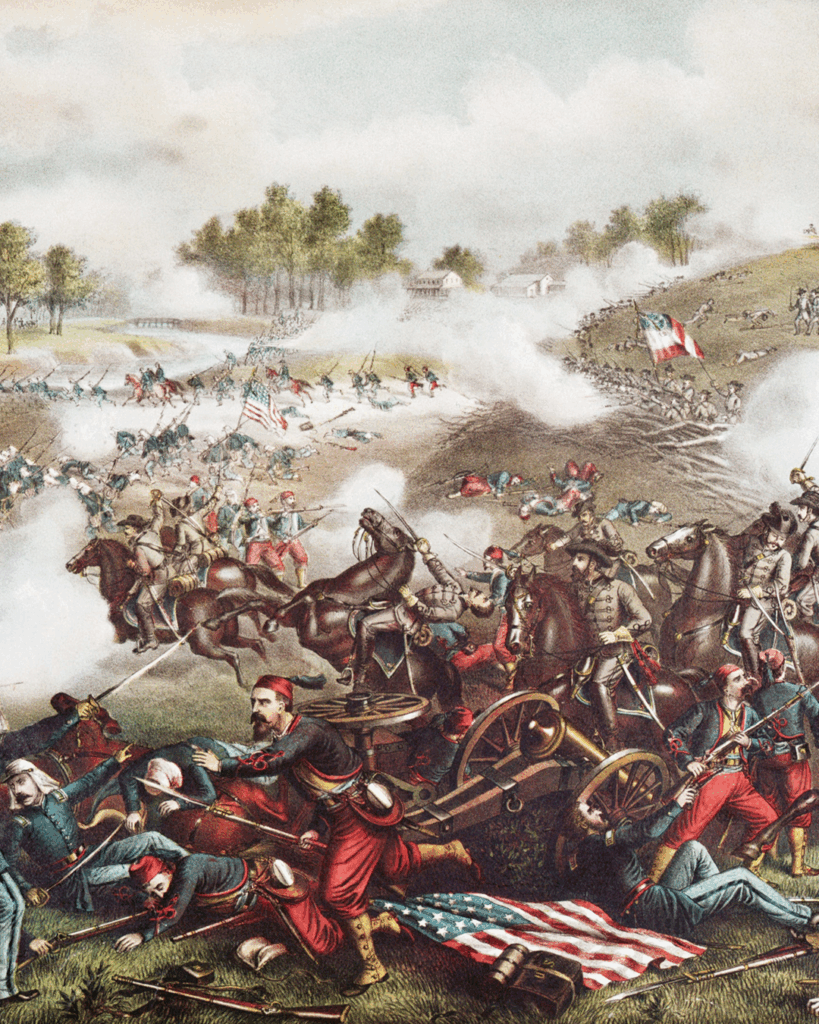

The Battle of Bull Run, the first major land battle of the American Civil War, was fought in Prince William County, Virginia, near the small stream known as Bull Run, close to the town of Manassas Junction. The battle took place 164 years ago today, on July 21, 1861, and marked a dramatic awakening for a nation that had expected a short and decisive conflict.

In the months leading up to the battle, tensions between the Union and the Confederacy had escalated. Following the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the Southern rebellion. The South, in response, rallied around the Confederate government, and both sides quickly began mobilizing forces.

Public pressure mounted in the North for a quick military victory that would crush the rebellion and restore the Union. Washington, D.C., was buzzing with optimism, and many civilians—including politicians and journalists—expected the war to be over in a matter of weeks. In response to this growing demand for action, General Irvin McDowell, commander of the Union Army of Northeastern Virginia, was ordered to advance southward and engage the Confederate forces.

The Confederate troops were under the command of General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, stationed near Manassas Junction to guard the vital rail lines connecting the Shenandoah Valley to Richmond. Another Confederate army, under General Joseph E. Johnston, was in the Shenandoah Valley, and thanks to the railroad—used for military troop transport for one of the first times in history—Johnston’s troops were able to reinforce Beauregard’s army in time for the battle.

Forces and Strategy

General McDowell led approximately 35,000 Union troops from Washington toward Manassas, aiming to surprise and overwhelm Beauregard’s force of about 22,000 Confederate soldiers. McDowell’s plan was to launch a feint attack on the Confederate right flank while his main force crossed Bull Run to strike the left flank and rear.

However, the Union army was largely composed of inexperienced volunteers. Many soldiers had enlisted for only 90 days and lacked training and discipline. McDowell himself was skeptical of their readiness, but he proceeded with the plan under political pressure.

The Confederates, for their part, were also relatively inexperienced, but they had the advantage of fighting defensively on familiar terrain. With Johnston’s reinforcements arriving just in time, their total strength increased to roughly 32,000 troops, evening the odds.

The Battle Begins

At dawn on July 21, McDowell launched a diversionary attack at Stone Bridge on the Confederate right while his main force marched north to cross Bull Run at Sudley Ford and attack the Confederate left. This flanking movement took longer than expected due to poor maps and unfamiliar terrain. By late morning, Union forces engaged the Confederate left, forcing a Confederate retreat toward Henry Hill.

Initially, Union forces achieved some success, pushing back the Confederate lines. However, Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson and his Virginia brigade arrived on Henry Hill and held firm. It was during this critical stand that Jackson earned his famous nickname: “Stonewall.” As Confederate lines faltered under Union pressure, General Barnard Bee is reported to have exclaimed, “There stands Jackson like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!” Though Bee was mortally wounded shortly after, the name stuck.

Jackson’s troops, supported by additional reinforcements, formed a strong defensive line atop the hill. Meanwhile, Confederate artillery under Colonel Edward Porter Alexander provided effective fire support, and Confederate cavalry under J.E.B. Stuart harassed Union flanks.

Union Collapse and Confederate Counterattack

Throughout the afternoon, Union forces launched repeated attacks on the Confederate position at Henry Hill, but confusion, exhaustion, and poor coordination hampered their efforts. The Union artillery, initially well-positioned, was overrun due to miscommunication and Confederate counterattacks.

The tide of the battle turned dramatically when fresh Confederate reinforcements arrived from the Shenandoah Valley. With superior numbers and strong defensive positions, the Confederates mounted a counteroffensive. Union troops, already fatigued and disorganized, began to fall back.

As the Confederate counterattack intensified, panic spread among Union ranks. Many soldiers, unaccustomed to the chaos of battle, broke formation and began to flee. The retreat quickly turned into a rout, with soldiers discarding weapons and equipment as they ran. Civilians who had come from Washington to watch the battle were caught up in the confusion and panic.

The Confederate forces pursued the retreating Union army for a short distance but, due to their own exhaustion and lack of organization, were unable to launch a decisive follow-up attack. By nightfall, McDowell’s army had retreated back toward Washington, ending the battle.

Casualties and Aftermath

The battle resulted in approximately 4,700 total casualties—2,700 Union and 2,000 Confederate—a staggering number at the time, shocking both sides. Many Americans, particularly in the North, had believed the war would be brief and relatively bloodless. Bull Run shattered that illusion.

For the Confederacy, the victory provided a surge of morale and confidence. Southern leaders interpreted the outcome as proof that their cause was just and that their soldiers were superior. However, they failed to capitalize on the victory with a major offensive, missing an opportunity to strike deeper into Union territory.

For the Union, the defeat was humiliating but also instructive. The panic and disorder of the retreat exposed the lack of preparation and military professionalism in the Union army. President Lincoln responded by reorganizing the military command and appointed Major General George B. McClellan to lead the newly formed Army of the Potomac, which would become the main Union force in the Eastern Theater.

The battle also signaled that the Civil War would be long, costly, and grueling. Both sides began to understand the scale of the conflict they were entering. Training, discipline, and logistics became priorities, and both the Union and Confederate governments intensified their war efforts.

Historical Significance

The First Battle of Bull Run holds great historical significance for several reasons:

- First Major Engagement: It was the first major battle of the Civil War and marked the point at which both the Union and Confederacy realized that the war would not be won quickly or easily.

- Symbolic Victory for the South: Although tactically indecisive in some ways, it was a clear Confederate victory that boosted Southern morale and gave credibility to the Confederacy’s fight for independence.

- Wake-Up Call for the North: The defeat forced the Union to take the war more seriously, leading to military reforms and the professionalization of the Union army.

- Introduction of Key Figures: The battle helped elevate the reputations of several Confederate commanders, particularly “Stonewall” Jackson, who would become one of the South’s most revered generals.

- Use of Railroads: The Confederate use of railroads to move Johnston’s troops from the Shenandoah Valley to Manassas was a pioneering example of strategic rail deployment, foreshadowing the increasing importance of rail logistics in the Civil War.

- Media and Public Perception: The battle was widely reported in newspapers, and its dramatic events, including the civilian spectators fleeing in panic, shaped public perception of the war’s brutality.

Conclusion

The Battle of Bull Run was a turning point in the early Civil War—not because of its strategic outcomes, but because it changed the nation’s understanding of what the war would entail. It dispelled illusions of a short conflict and ushered in a new era of prolonged and bloody warfare.

Both the Union and Confederacy emerged from the battle with valuable lessons. The Union realized the need for trained troops and strong leadership, while the Confederacy, despite its victory, recognized that future battles would demand even greater coordination and effort.

Bull Run set the tone for the Civil War—a conflict that would stretch over four years and claim hundreds of thousands of lives. It was the beginning of America’s most devastating internal struggle and a sobering reminder of the cost of division.