February 10, 1763: The Treaty of Paris Ends the French & Indian War—And Kicks Off the American Revolution

The Treaty of Paris and The American Revolution This year we commemorate the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It was signed in the midst of the American...

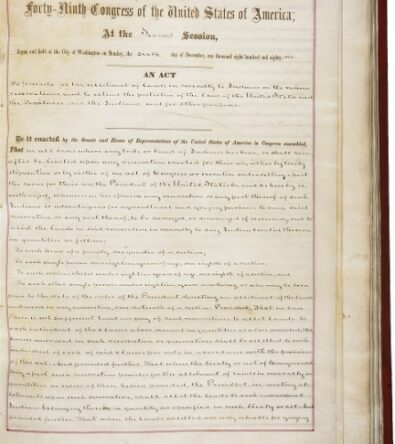

February 8, 1887: The Infamous Dawes Act Becomes Law, Targeting Native-American Reservations for Extinction

The Dawes Act We’ve written a number of stories about the slow and steady erosion of Native-American tribal lands in the 19th century due to the encroachments of white settlers—the natural...

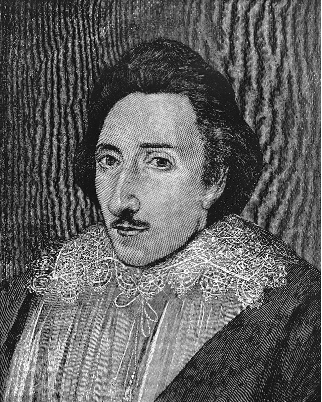

Remembering Samuel Argall

The history of the Jamestowne Colony has largely receded from our national consciousness, replaced by the story of the Pilgrims, the story of the American Revolution, and so forth. This year in...

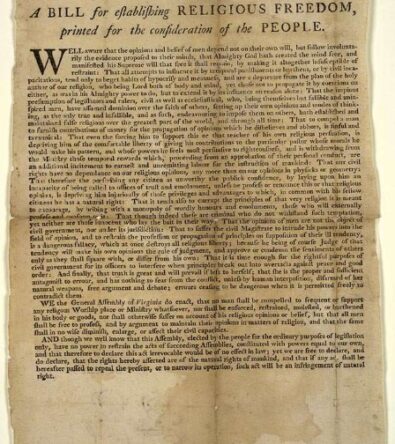

The 240th Anniversary of Thomas Jefferson’s Act for Establishing Religious Freedom

On January 16, 1786, the State of Virginia enacted a ground-breaking piece of legislation known as the Act for Establishing Religious Freedom. The Virginia statute is noteworthy for the man who...

Remembering Mary Rowlandson

For many Americans, the history of 17th Century New England conjures up images of hardy immigrants making their way across the ocean, taming nature, and bringing European cultural, social and...

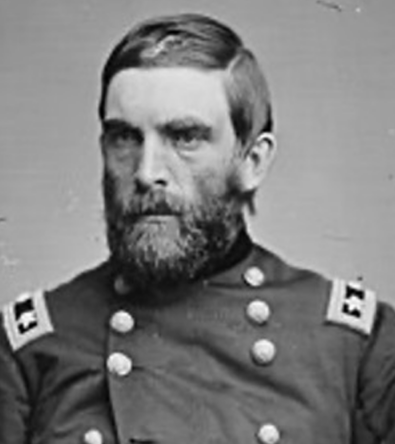

Remembering Grenville Dodge

The American Civil War produced a long list of generals who led men into battle, and in some cases became American heroes: Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Philip Sheridan come to...

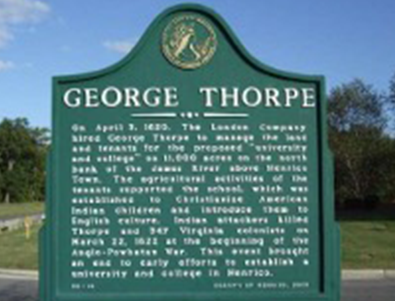

Remembering George Thorpe

One of the most tragic events at the Jamestowne Colony in its early years was the Massacre of 1622, in which many settlers lost their lives. One of them was George Thorpe, who had worked tirelessly...

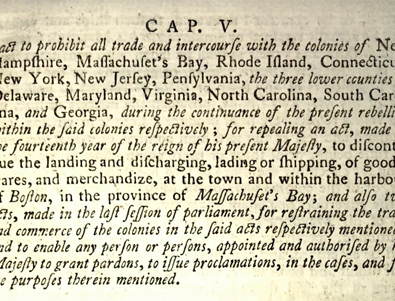

The 250th Anniversary of the Prohibitory Act of 1775: King George III Takes Off the Gloves

While it was only one paragraph long, the Prohibitory Act of 1775 was a bombshell for the American colonists who were now at war with their mother country, Great Britain. In the Fall of 1775,...

Remembering Red Cloud

We’ve written before about some of the greatest Native-American warriors of the 19th century: Crazy Horse, Chief Joseph, and Quanah Parker, to name a few. Today we write about another of the great...

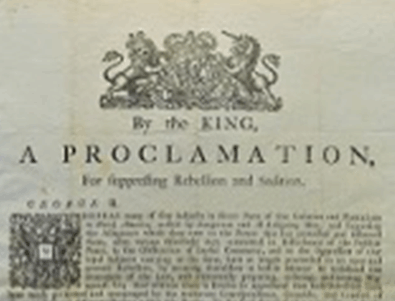

December 1775: Great Britain and America Exchange a War of Words, as the Revolutionary War Intensifies

Months after the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” kicked off the American Revolution in April 1775, a large number of colonists—a very large number– were still reluctant to declare...