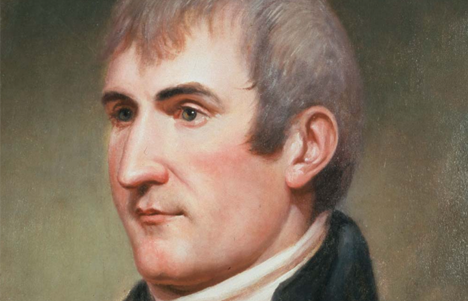

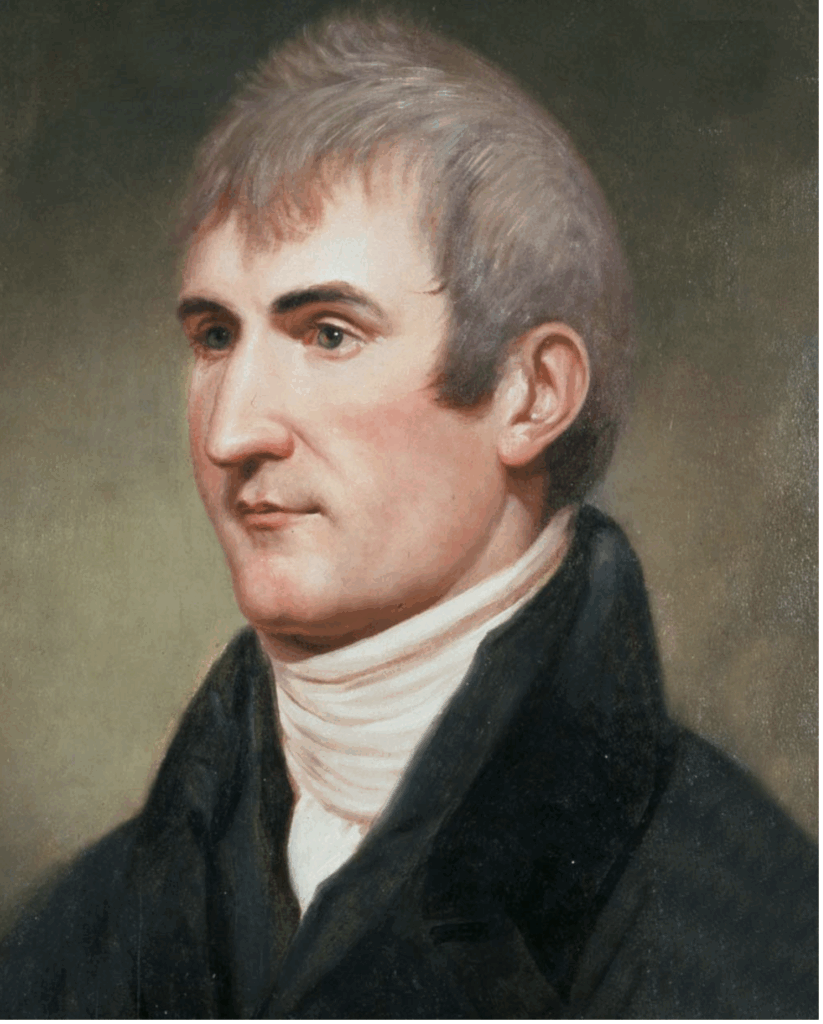

Commemorating the 200th Anniversary of the Birth of Lewis

In the history of the American West (by which I mean west of the Mississippi), two events arguably were the starting point for the western expansion of America, and the migration of millions of settlers from east to west over the course of the 19th Century: the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and the Lewis & Clark Expedition of 1805-1806. There is no national holiday for either of these two events, much less any 21st Century commemorations of the two men who led the “Corps of Discovery” in search of a navigable route to the Pacific Ocean: Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) and William Clark (1770-1838). So today, we take time out to celebrate the 200th Anniversary of the birth of Lewis, born on August 18, 1774.

Lewis was born on Locust Hill Plantation in Virginia. Following the death of his father five years late, he and his mother moved to Georgia, but he returned to Virginia at age 13 to pursue an education. He entered the military in 1794, where he rose to the rank of captain, then in 1801 became Secretary to President Thomas Jefferson. It was during that service that Jefferson approved the Louisiana Purchase, by which America took control of over 800,000 square miles of land that now comprise almost the entirety of the mid-West. This proved the stimulus for Jefferson’s decision to launch an expedition to discover and survey these newly-acquired lands, and return with as much information as possible about the possibility of a route to the Pacific. Lewis and Clark were further commissioned to explore the areas west of the Purchase, and determine whether there was a waterway that would lead to the Pacific. Lewis, partnering with his former commander William Clark, launched the expedition in 1806, and over the next two years sent back to Jefferson and Congress glowing reports— and artifacts— that transformed America’s understanding of the West, and triggered the massive movement of people from East to West (despite the fact that no waterway route to the Pacific was ever discovered).

Following the Expedition, Lewis’ life was difficult. Tasked with writing a full account of the Expedition, he dithered, and never finished it. Jefferson appointed him to be the Governor of the new Louisiana Territory, but Lewis ran into political conflicts that marred his administration, and led to a decision by the War Department to deny Lewis’ requests for reimbursement of his expenses (they were, however, ultimately paid two years after Lewis’ death). Lewis became depressed and disenchanted. During this period of political squabbling, on October 11, 1809, during a trip from St. Louis to Washington D.C., Lewis died of gunshot wounds at a roadside inn in Tennessee. Historians continue to debate whether his death was a suicide. The circumstantial evidence lends support to that conclusion, but his family contended that it was murder. His body was exhumed in 1848, and a commission that investigated the cause of death concluded that it was “more probable” that Lewis killed himself.

Whatever the circumstances of his death, Lewis was a towering figure in the first decade of the 19th Century, the leader of one of the greatest expeditions in American history. For that, we celebrate the 200th anniversary of his birth on this day.