As we enter the Fall season, thoughts of many Americans turn to the upcoming holidays, especially Thanksgiving, when we traditionally honor the memory of our Pilgrim ancestors who came on the Mayflower in 1620 and founded the Plymouth Colony. The Plymouth Colony was short-lived, as it ultimately merged into the much bigger Massachusetts Bay Colony to the north. Unlike the Pilgrims, the Puritans of the Bay Colony were zealous adherents to the Puritan faith, and aggressively sought to proselytize to the Native-Americans and convert them to Christianity. To most of the Puritans, Native-Americans were godless savages in need of saving through adoption of the Christian faith. Those efforts were largely unsuccessful, although members of some of the New England tribes did “christianize” (and were pejoratively referred to as “Praying Indians”).

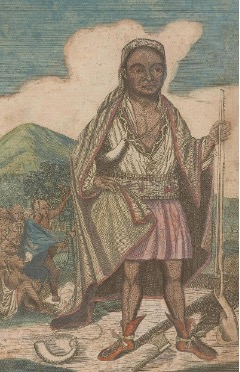

One person who seemingly adopted the Christian faith—or paid lip-service to it– was Metacom. Metacom was the sachem (chief) of the Wampanoag tribe, the tribe that famously had helped the Pilgrims in the early years of Plymouth Colony, and whose people joined the Pilgrims in 1621 in the feast that later became known as “Thanksgiving.” The sachem at the time of that feast was Massasoit, who had two sons, Wamsutta and his younger brother Metacom. When Massasoit died, and the older son died Wamsutta shortly thereafter, Metacom became sachem of his tribe in 1662.

As sachem, Metacom initially gave every indication that he wanted to live harmoniously with the people of Plymouth Colony. To show his openness to that, he had taken the Christian name of Philip, and he came to be known to the English settlers as King Philip. There is no evidence, however, that Metacom actually converted to the Christian faith. Despite King Philip’s support for open trade relations between the Wampanoags and the Plymouth settlers, the leaders of the Plymouth Colony came to see the Wampanoags as a threat as the tribe began amassing weapons and ammunition. In 1671, King Philip was hauled before the Plymouth leaders and forced to turn over some of his tribe’s weapons and ammunition, and to obey the laws of Plymouth Colony. An underlying motive of forcing the surrender of weapons was that many colonists had their eyes on lands to the west, some of which was occupied by the Wampanoags, and while treaties were often used to acquire Indian lands, many Indians were hostile to English encroachments on their lands. Indian attacks were an ever-present concern of the colonists.

For the next five years, tensions rose, and Metacom became increasingly opposed to the colonists’ expansionist agenda. Thus he began to rally his people, as well as neighboring tribes, in an effort to form an alliance of tribes that could resist the steady migration of white settlers onto their tribal lands. Matters came to a head in June 1675, when a Plymouth Colony court found three Wampanoags guilty of murdering an Indian interpreter by the name of John Sassamon, who was found dead in a swamp. Following a trial of sorts, the three Wampanoags were found guilty sentenced to death. The judge who presided over the trial was Josiah Winslow, the son of Mayflower passenger Edward Winslow. The three Wampanoag men were quickly taken to the gallows and hung by the neck. The rope on one of the men’s neck broke, and his life was spared. The other two men died.

That was enough for Metacom, and he immediately commenced all-out war against the colonists. Battles raged over most of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and Rhode Island over the course of the next year. Among other targets, Indian raids were launched against the towns of Swansea, Rehoboth, Taunton, Middleborough and Dartmouth. Outraged, the colonists– well-armed and well organized– pursued Metacom with a vengeance, killing many Indian men, women and children, attacking their villages, burning their homes and destroying their crops. Indian warriors were equally deadly in their war-making, and both sides committed many atrocities. A contemporary account of the War written by Nathaniel Saltonstall recounted that at Narragansett, “not one house was left standing. At Potuxit, “none [was] left.” The town of Marlborough was “wholly laid in ashes,” and Deerfield was “wholly ruined.” Saltonstall chillingly wrote that of the dead, “many have been destroyed with exquisite Torments and most inhumane Barbarities.” Perhaps the worst battle was in December 1675 near Mt. Hope, Rhode Island, otherwise known as the Great Swamp Fight. Colonists attacked a Naragansett village where hundreds of men, woman and children were then living, and burned it to the ground; most of the inhabitants were burned to death.

From all this death and destruction, King Philip’s army gradually was depleted, and Metacom was forced to flee. After months of being chased across the countryside, on August 12, 1676 Metacom was finally hunted down and cornered in Mount Hope, where he was shot to death. Ironically, the man credited with killing Metacom was one of the “Praying Indians” by the name of John Alderman. At Alderman’s side was Caleb Cook, grandson of Mayflower passenger Francis Cooke. Caleb had fired first, but missed. One account of the killing reported that when troops arrived on the scene, Metacom was “on his face in the mud and water, with his gun under him.” Grusomely, Metacom’s body was mutilated, his head cut off, and body parts taken to put on display. Metacom’s severed head was mounted on a pike at the entrance to the Plymouth settlement. Alderman was given Metacom’s hand as a trophy. Metacom’s warriors quickly dispersed, either to join other tribes, or in some cases they were forced into slavery. Metacom’s family members were not spared. His wife and son were sold into slavery in Bermuda.

King Philip’s War effectively ended any semblance of peace between the colonists and neighboring tribes. Because of its sheer brutality, the War is still strikes a raw nerve with the Wampanoags. Thanksgiving is considered a National Day of Mourning by the tribe. A number of years ago, the U.S. Department of Defense analyzed the deaths per thousand people of all the major wars fought on American soil, and determined that King Philip’s War resulted in the highest number of deaths per 100,000 of all such wars—dramatically higher than the Civil War and the American Revolution. According to the DOD’s statistics, Indians suffered 15,000 deaths per 100,000. By comparison, only the Civil War produced only 857 deaths per thousand.

One of the leaders of the colonists’ army in King Philip’s War was Benjamin Church. He was the grandson of Mayflower passenger Richard Warren. He had been a long-time friend of the Indians, and had friendly relations with Metacom. He also was respected by the leaders of Plymouth Colony. Following the war, he wrote a history of the war, which was later edited and published by his son Thomas Church. The book is difficult reading, but is considered one of the seminal first-person narratives of the war. You can find the book online (for free) at hathitrust.org.

Is there a lesson in all this? King Philip’s War was the culmination of decades of culture clashes between English settlers and Native-American tribes. The settlers often viewed Native-Americans as inferior people who needed to be subjugated, converted, or pushed aside. Many Native-Americans saw the colonists as intruders who sought to take their lands and destroy their culture. One person who saw the possible repercussions of these culture clashes was Reverend Roger Williams, who was himself a religious non-conformist who was banished from the Bay Colony in the 1640’s and who proceeded to form his own colony, Providence Plantations, in today’s Rhode Island. In a book he wrote in 1643, “A Key Into the Language of America,” Williams chastised Bay Colony colonists for their airs of superiority towards Native-Americans in words that ring true today:

“Boast not, proud English, of thy birth and blood;

Thy brother Indian is by birth as Good.

Of one blood God made Him, and Thee, and All,

As wise, as fair, as strong, as personal.”

Had the English leaders only listened to Roger Williams, and took his words to heart, perhaps the history of New England would have been quite different. But it was not to be.

And so today we honor the memory of Metacom, the powerful leader of the Wampanoag tribe, who died this day on August 12, 1676 at the age of 38.