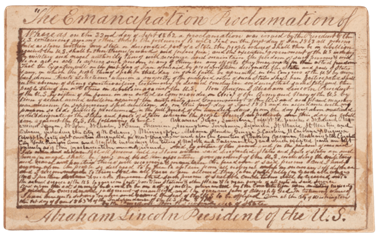

This month in 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, one of the most important Presidential acts in American history. Since the enactment of the United States Constitution in 1789, the country had wrestled with the issue of slavery, as the nation experienced decades of increasingly violent confrontations between slaver-holders (primarily in the Southern states), and Northern anti-slavery advocates. A flash point was the admission into the Union of Western states in the first half of the 19th century, where the legality of slavery was still an open question. In my prior blog posts, I’ve written about the infamous Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which gave new states the possibility of legalizing slavery (codifying the arguments of Stephen Douglas and other political leaders who espoused the concept of “popular sovereignty”). Immediately following the passage of that Act of Congress, a civil war of sorts broke out in Kansas, which came to be known as “Bleeding Kansas.” The secessionist fervor in the South increased over the next five years, culminating in the secession of South Carolina in December 1860, following Lincoln’s election to the presidency in November 1860. The Civil War had begun.

Up to the beginning of the war, President Lincoln had been conflicted on the issue of slavery, having witnessed its horrid reality first hand when he lived in Kentucky and Illinois, including the infamous slave markets in which husbands, wives and children were separated and sold to the highest bidder. Yet, Lincoln understood that slavery was a political morass that had plagued the nation for a century, and that had caused Congress to stop short of including any prohibition of slavery in the Constitution (Congress compromised by barring the slave trade commencing 20 years after the date the Constitution was enacted). Some of our Founding Fathers were similarly conflicted, as several of them were slaveholders themselves, but privately acknowledged that slavery needed to stop—perhaps gradually, on its own steam, without the need for any legislative action, and perhaps coupled with the forced removal of freed slaves to places outside of the United States, or to remote areas of the West. In one example, the Marquis de Lafayette proposed to George Washington that slaves be expatriated to French Guiana, an idea that received a lukewarm response from Washington. Similar ideas had been floated by Thomas Jefferson, who thought slavery would disappear of its own accord with the passage of time, as the slaveholders of the South acquired lands in the West where slavery was not practical—no cotton plantations were likely to be created in the territories west of the Mississippi, he surmised. In his wrongheaded thinking, the country could avoid the political fight over slavery if it just waited out the gradual disappearance of slavery with the passage of time. He was wrong, of course, as the political in-fighting over slavery began surfacing shortly after Jefferson consummated the Louisiana Purchase, and Lewis & Clark sent back glowing reports on the opportunities that lay ahead for Americans through settlement of the western territories.

As for Lincoln, in the famous Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858, and again during the 1860 campaign for the presidency, he avoided any explicit promise to end slavery if elected President. On the contrary, he expressed his willingness to leave matters as they stood—accepting slavery in the South, while holding the line on any future expansion of slavery in the West. He held to this position after being elected. During the first two years of the war, he and his allies adhered to the narrative that the Civil War was not about freeing the slaves, but about preserving the Union. On the other side, the Confederacy claimed that the Civil War was over “states’ rights,” not the perpetuation of slavery. In the end, both of these narratives were shelved: the Union, needing more troops, began recruiting freed and enslaved blacks to join the Union Army, on the promise of emancipation, while Southern politicians—including President Jefferson Davis—ultimately said that the Confederacy might concede the issue of slavery if the Union would otherwise leave the Southern states alone (and effectively independent). Lincoln would have nothing to do with such a compromise, and in several meetings with leaders of the Confederacy he and his advisors made clear that no peace could be agreed to that didn’t include the abolition of slavery, everywhere.

For the Union’s political leaders to declare that a main purpose of the Civil War was to free the slaves was a major turning point in the war. For Lincoln to announce such a position, he had hoped for popular support, and for proof that the Union was going to be able to win the war (some of his advisors having told him that it would look like desperation for Lincoln to declare his intent to end slavery while he was losing the war). During the first two years of the war, however, the Union couldn’t make that case: it was losing major battles in the East, and Lincoln was running through Generals who either refused to fight (General George McClellan), or were inept or weak military leaders (Generals Ambrose Burnside and John Pope, to name a few). The travesty of the Battle of Antietam in September 1862 is one example.

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln had “pre-announced” the Emancipation Proclamation, giving the Confederacy 100 days to cease warfare and return to the Union. His preliminary Proclamation of September 22 was short, but powerful. He said:

“That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

What explains the timing of Lincoln’s issuance of the preliminary Proclamation? Not coincidentally, it was issued just five days after Antietam, in which over 22,000 soldiers were killed, wounded or were missing in action. A Library of Congress discussion surmises that the timing was “partly in response to the heavy losses inflicted in the Battle of Antietam.” Lincoln no doubt meant his preliminary Proclamation to enable the Union Army to establish black regiments comprised of freed or enslaved blacks, which would greatly help the Union Army in the Southern Campaign that was then under way. In the next few months, the first black regiments were recruited in South Carolina and Tennessee. Famed freedom fighter Frederick Douglass added momentum to the recruitment effort by publicly encouraging black men to enlist. By the end of the war, historians estimate that almost 180,000 black soldiers had served, or were serving, in the Union Army, and there is no doubt that the Union Army’s ultimate victory over the Confederate Army was significantly aided by these black regiments (the victory at Vicksburg being one example, where black troops played a role). After the preliminary Proclamation issued, the war increasingly became a numbers game, as the Union Army’s superior troop strength was taking its toll on the Confederate armies.

Yet, in the latter part of 1862, there were no signs that the Confederacy would stand down. Indeed, just 3 months after the preliminary Proclamation issued, Confederate troops under the command of General Robert E. Lee crushed the Union Army under the command of Ambrose Burnside at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 11-15, 1862. Hearing of the slaughter of Union troops at Fredericksburg, Lincoln saw no basis not to make good on the preliminary Proclamation’s announcement that the complete abolition of slavery would become effective on January 1.

The final Emancipation Proclamation issued on January 1, 1863 first announced what states were still in active rebellion:

“I, Abraham Lincoln… do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days… order and designate as the States and parts of States therein are this day in rebellion against the United States:”—and he then named them.

Lincoln then recited these immortal words:

“I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within these designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free.”

The Proclamation also included several admonitions: first, that freed slaves should not resort to violence unless to defend themselves; second, that they should seek employment in some form; and third, that they should consider joining the Union’s armed services.

Lincoln ended the Proclamation with an invocation of God and country:

“And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.”

Following the Emancipation Proclamation, the fortunes of war turned, as the Union Army successfully waged war in the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, and General Ulysses S. Grant was winning battle after battle in the West, culminating in Grant’s victory at the Battle of Vicksburg in July 1863. Several months later, in his famous Gettysburg Address delivered from a stage at the battlefield on November 19, 1863, Lincoln renewed his commitment to winning the war, and preserving the Union (interestingly, without mentioning the issue of slavery). The stage was now set for the final push to win the war, preserve the Union, and abolish slavery. This month, we celebrate one of the greatest events in American history. The Emancipation Proclamation re-defined what the Declaration of Independence meant when it said “We the People.” It would take another three years for the 13th Amendment to the Constitution to be ratified in December 1865. President Lincoln, assassinated in April 1865, did not live to see this final step taken to guarantee freedom to black persons, but it was his courageous act in signing the Emancipation Proclamation that made it all possible.