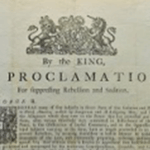

It was called the “Era of Good Feelings.” The first term of the presidency of James Monroe was a period of economic growth, western expansion, and infrastructure improvements, and President James Monroe became a revered figure in American politics. In his second term of office, however, Monroe was consistently stymied in carrying out his agenda by an antagonistic U.S. Congress, and he became increasingly powerless. As well, England, Spain and other foreign powers were engaging in maritime and colonization activities in the Western Hemisphere that many political leaders viewed as a threat to America’s hegemony. In South America in particular, the independence movements in several countries were causing European monarchs to undertake more vigorous efforts to reassert control over their colonial empires, and to form alliances that would serve to curtail any further moves towards democracy.

All of this was causing consternation in the White House. President Monroe and his advisors—most notably his Secretary of State John Quincy Adams—believed that any attempt by European powers to flex their muscles in the Southern Hemisphere must be met forcefully by the United States, if not militarily. The situation was tricky from a diplomatic standpoint, because the U.S. had treaties and alliances that might be imperiled if America went to war, or otherwise was perceived as supporting democracy in the Southern Hemisphere. As well, the U.S. had its own colonial ambitions, Cuba being a prime example: it was a Spanish colony tilting towards independence, and many American political leaders thought the time was ripe for a U.S. takeover of the island itself.

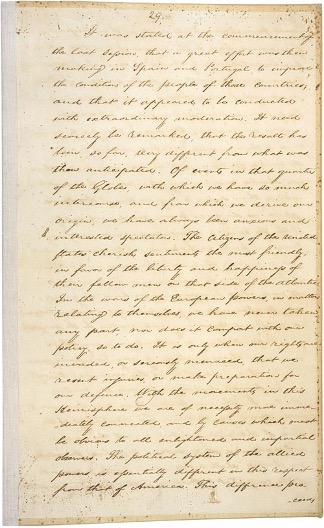

If was at this moment that Monroe and his advisors decided to make a bold new statement of America’s foreign policy that would draw a very bright line between the “Old World” of Europe, and the “New World” of the Western Hemisphere. After weeks of internal discussion and debate, On December 2, 1823, Monroe used the occasion of his seventh annual State of the Union Address to articulate America’s new policy, which later came to be known as the “Monroe Doctrine.” In one sentence, he summed it up: the continents of North and South America “are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European power.” Monroe clarified that the U.S. would not affirmatively interfere with any existing colonies or dependencies, but issued a warning that any political intervention by any European power in the affairs of any country in the Western Hemisphere would be considered “dangerous to our peace and safety.” The message was clear: stay away.

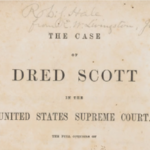

Monroe’s presidency ended in 1824 with the election of John Quincy Adams. But the doctrine that bears his name has continued to define American foreign policy to this day. Ironically, in the ensuing decades of the 19th century, the Monroe Doctrine was loosely relied upon to justify America’s own conquests of North American territories in furtherance of our “manifest destiny.” Under this theory, in asserting control over lands previously claimed by Spain, France, England, even Russia, the U.S. was merely protecting its own right to occupy lands it was “destined” to own and control. As for native-Americans, while they were not the sovereign states of the “Old World” Monroe had been focused upon in articulating the Monroe Doctrine in December 1823, they became the primary victims of America’s relentless pursuit of its manifest destiny. But we cannot blame Monroe for later misuses of the Monroe Doctrine—he died in 1831, just two years into the presidency of Andrew Jackson, when “manifest destiny” began to be the rallying cry for western expansion.

What did Monroe truly intend? The words he spoke in his Seventh State of the Union Address have been interpreted in ways he could not have imagined. But for better or worse, his Doctrine has left a lasting legacy, one that has defined his presidency down through the ages.

So on this day, we commemorate the announcement of the Monroe Doctrine, a seminal event in the history of 19th century America.