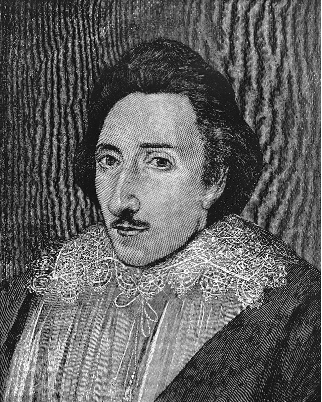

The history of the Jamestowne Colony has largely receded from our national consciousness, replaced by the story of the Pilgrims, the story of the American Revolution, and so forth. This year in particular, our 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence will take center stage—no argument there—with many commentators and historians remarking on how our country was “founded” in 1776. Well, not so fast. The first permanent English settlement in North America was the Jamestowne Colony, founded in 1607, a century and a half before the Revolution. Today, we want to take a few moments to honor the memory of one of the courageous men and women who made that settlement possible: Samuel Argall, who died this day on January 24, 1626, four hundred years ago this day.

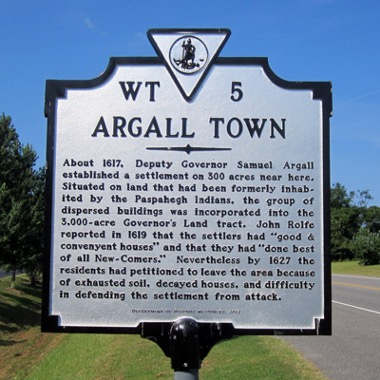

Samuel Argall was first and foremost an experienced sea captain, who became active both politically and militarily in the affairs of the Jamestown Colony. He served as its Governor from 1617-1619, during which time he faced many challenges. In a letter he wrote in March 1617 to the Virginia Company (the organization overseeing the Colony’s affairs back in London), he expressed dismay about “the ruinous condition I found the colony by the carelessness of the people and lawless living.” He also lamented that the crops upon which the colonists depended “will hold out but 3 years, and [the colonists] can’t clear more [land] for want of tools.” Argall pushed the colonists hard to improve conditions, and in the process, he created a backlash. He was forced to step down as Governor in 1619 and returned to England following accusations of misconduct. He was cleared of those charges, and later was knighted by King James I in 1622. He died at sea on January 24, 1626, and was buried in Cornwall.

The longer version of Argall’s story begins in the year 1580, when Argall was baptized in East Sutton, Kent. He was the son of Richard Argall (1536-1588) and his wife Mary Scott (d. 1598). Mary was from an aristocratic family, the daughter of Sir Reginald Hall. In his twenties, Argall was an active ship’s captain, and led a number of Atlantic crossings.

Argall arrived in Jamestowne Colony in July 1609 as part of the “Third Supply,” and he became one of the Colony’s early leaders. Of the nine ships that had set sail for Virginia in May 1609, one of them, the Sea Venture, was believed to have been lost at sea when violent storms overwhelmed the fleet near the island of Bermuda. It was not until a year later that the survivors of the shipwreck found their way to the Colony after spending many months stranded on Bermuda, and building new ships to carry them on to Virginia. Until then, the other passengers who had already arrived in Jamestowne assumed that the passengers on the Sea Venture were dead.

October 1609: Samuel Argall Returns to England; He Reports the Loss of the Sea Venture

Argall returned to England in the Fall of 1609, arriving there in October. In a report he delivered to the Virginia Company shortly after his arrival, Argall (incorrectly) reported the loss of the Sea Venture, which was carrying much needed supplies, as well as the new Governor of the Colony and other passengers. The loss of the Sea Venture was considered a disaster. Compounding the negative news, Argall’s returning fleet also carried thirty men who had been sent to Virginia as laborers, but who had been rejected by the Colony. The combination of lost supplies and lost manpower caused major concerns for the Virginia Company. It was with great relief when, in 1610, news came back to London that the Sea Venture has not been lost, and it had made its way to the Colony after all. Many stories have been written about the saga of the Sea Venture, which became the basis for Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest.

Argall returned to Virginia in the Spring of 1610, joined by the Colony’s new Governor, Thomas West, Lord de la Warre, to Virginia. When they arrived, they learned that the Colony had been decimated by the effects of the “Starving Time” of the winter of 1609-10, when most of the colonists died of disease and starvation. This time, the disaster was real, and it shook the Virginia Company’s confidence badly when news of this latest setback traveled back to London. It took concerted efforts by the Company, and the hard work of an influx of new settlers, to restore the Colony to a semblance of civilization.

June 14, 1613: Samuel Argall Leads Expedition to Capture Pocahontas

One of Samuel Argall’s most inglorious actions was a misguided effort to negotiate with Chief Powhatan for the return of prisoners, weapons and tools that the Powhatans had seized, by ransoming his daughter. Argall had been in contact with some of the neighboring tribes who had soured on their alliance with the Powhatans, including the Patawomack tribe located on the Potomac River. Argall got wind that Pocahontas was staying with the Patowomacks, and in June 1613, he and his men sailed up the Potomac to meet with the tribe. Once there, on June 13 Argall went to the tribe’s leader, Iopassus (also known as Japazaws), and offered him a deal: capture Pocahontas in exchange for an alliance with the colonists against Chief Powhatan. Iopassus took the deal. He went to Pocahontas and offered her a copper kettle as the “bait” to get her on board. Once on board, she was captured and held for ransom. The ploy failed, however, as Chief Powhatan refused to meet the colonists’ demands that he return the weapons and tools that he had taken from them. The stalemate lasted an entire year, during which time Pocahontas remained a captive of the colonists.

This episode proves the law of unintended consequences. In captivity, Pocahontas met Jamestowne colonist John Rolfe, fell in love with him, and agreed to marry him. She also agreed to convert to Christianity and change her name to Rebecca. One can imagine Captain Argall’s chagrin that the capture of Chief Powhatan’s daughter failed to bring the Chief to the bargaining table, and that Pocahontas would ultimately turn her back on her father and sail away to England shortly after her wedding to Rolfe.

June 9, 1617: Samuel Argall Reports to the Council for Virginia on the State of Affairs at Jamestowne Colony

In mid-1617, Argall had returned to Jamestowne from England, and in a letter to the Council of Virginia in London, he made several quick observations: there was “great plenty and peace” in the Colony, and he “found your people well.” He observed that “silk worms thrive exceedingly,” that “hemp and flax will grow well here,” that there was “excellent wheat and barley,” and that “cattle thrive.” That said, he noted several problems needing attention. First, there was no minister to administer the sacraments (Chaplain Alexander Whitaker having just drowned), so Argall asked that the English church give the Reverend William Wickham the power to administer the sacraments, “here being no other person.” Also, he found “all boats etc. out of repair,” and he requested that the Company send “100 men with tools & etc. that he will provide with victuals.”

On a more disturbing note, Argall reported that when he arrived back at the Colony, he had sent Tomakin, a Powhatan holy man (otherwise known as “Tomoco” or “Uttamatomakkin”) to tell Chief Powhatan’s brother Opechancanough of his arrival. Argall discovered, however, that Tomakin had been “railing against English people and particularly his best friend Thomas Dale,” and apparently causing Powhatan to think ill of the English settlers. Argall went to some lengths to address the issue, the result of which was that “all [Tomakin’s] reports are disproved before Oppanchancano [sic] and his Great men, whereupon (to the great satisfaction of the Great men) Tomakin is disgraced.” Previously, Tomakin had been held in high regard, and had accompanied Pocahontas to London in 1616 (supposedly with the secret purpose of counting the number of people in England and reporting that back to Chief Powhatan, and finding out if Captain John Smith was still alive). While in London, Tomakin and Pocahontas attended a theatre performance together, and met King James I; Tomakin later complained that the King should have given him a present!

Whether Tomakin was in fact “disgraced” is a question mark, in light of the fact that the following year, Chief Powhatan died, Opechancanough took over as Chief, and he began plotting what came to be known as the Massacre of 1622. Clearly, someone had convinced the Oppechancanough that the English people were enemies of the Indian peoples, and should be annihilated, and Tomakin seems to have been a likely suspect.

October 20, 1617: Argall Pardons George White from the Death Penalty for “Running Away to the Indians”

A recurring problem during the early years of the Jamestowne Colony was desertion— either men leaving the Colony for parts west, returning to England as stowaways, or joining one of the local tribes. In the case of colonist George White, he was caught “running away to the Indians with his arms and ammunition,” re-captured by the Colony, and sent to trial for his misdeeds. He was saved, however. On October 20, 1617, Governor Argall issued a pardon to him, noting that he was issuing the pardon even though the facts “deserve death according to the express articles & laws of this Colony.” Also pardoned that day were two other colonists, one for “stealing a prisoner woman,” and one for “stealing a calf & running to Indians.”

The rest of Argall’s day on October 20 was spent issuing various commissions and appointments. He made Nathaniel West the Captain of the Lord Generals, and he commissioned Nathaniel Pool to be a Sergeant Major General, and appointed William Powell to be Captain of his Guards. Finally, he commissioned Francis West to be the “maker of ordinance.”

February 20, 1618: Governor Argall Commissions William Craddock to Be Provost Marshall of Bermuda City

On February 20, 1618, Argall issued a commission to William Craddock to serve in the key position of Provost Marshall of Bermuda City, later known as Charles City. Bermuda City was first visited by Thomas Dale, and according to colonist Ralph Hamor, the settlement was “begun about Christmas last [1613].” Dale created several different “hundreds” out of the lands on both sides of the James River, including what came to be known as Berkeley Hundred. Bermuda City was by far the most active of the settlements Dale carved out, and within a short period of time in had more inhabitants than Jamestowne itself. So it must have been an honor, indeed, for Cradock to be appointed Provost Marshall in 1618.

Among the inhabitants of Bermuda City was George Yeardley, as well as various farmers and men “who labor generally for the colony, among whom some make pitch and Tarr, Pott-ashes, Chark-coale, and other workes.” It was a busy place, and Governor Argall granted Craddock broad authority to govern the affairs of the city: the Governor’s commission stated that Craddock was given “all power and Authority to Execute all Such Offices, Duties, and Commands belonging to the place of Provost Marshall with all privileges and prehemynences thereto belonging.” Craddock’s authority also included the power to quell “all Mutinies, factious Rebellions and all other Discords contrary to the quiet and peaceable Government of this Comon-Weale.” The Commission reflects Argall’s high regard for Craddock, stating that “it is most expedient and necessary to have an honest and Carefull provost Marshall to whose charge and Safe Custody all Delinquents and prisoners of whatever Nature or Quality soever… are to be committed.” Argall clearly viewed Craddock as someone on whom he could rely to maintain law and order in Bermuda City.

Although Bermuda City continued to prosper, Governor Argall apparently favored Jamestowne itself as the center of business and government. The same year as he appointed Craddock to be Provost General of Bermuda City, Argall wrote that he preferred Jamestowne, and that he would be taking steps to strengthen it as a good healthy site of government. All of this became academic a few years later, when the Massacre of 1622 devastated Charles City, and the location was abandoned by scores of survivors of the massacre. The census of 1625 showed only 44 people still living there. In the meantime, Jamestowne—which had been largely spared from the massacre— grew into its own as the center of government.

May 10-18, 1618: Argall Issues “Proclamations or Edicts” to Regulate Colonists’ Behavior

Going well beyond the regulations that had been in place before he became Acting Governor, on May 10, 1618 Argall issued the first of several “Proclamations or Edicts,” as they were labeled in the Records of the Virginia Company. The May 10 Proclamation tersely ordered “every person to go to Church Sundays and holidaies or lye neck & heels on the Corps du Guard the night following & be a slave the week following 2nd offence a month, 3rd a year and a day.”

Argall’s “Proclamations and Edicts” imposed decidedly stiff punishments for those who failed to attend church. It was just the opening salvo, however. On May 18, 1618, he issued seven more sweeping “Proclamations,” which prohibited colonists from:

- “private trucking [trading] with Savages & pulling down pallisadoes [palisades, the fortified walls erected to protect the colonists from attack]”

- “teaching Indians to shoot with guns on pain of death to learner & teacher”

- Going “armed to Church & to work”

- “shoot[ing] but in defence of himself against Enemies till a new supply of ammunition comes, on pain of a years Slavery”

- “go[ing] aboard the Ship now in James Town without the Governor’s leave”

- “trading with the perfidious Savages, nor familiarity, les they discover our weakness.”

Taken as a whole, Argall’s “Proclamations and Edicts” reflect several things about the state of affairs in the Colony, and what Argall believed was needed to remedy the situation: i) the threat of Indian attacks was a major concern; ii) colonists’ contacts with Indians were believed to increase the risk of attacks; and iii) it was thought that colonists needed to get closer to God, as a means of overcoming the adversities the Colony was facing.

Looking back, we know that notwithstanding the “Proclamations and Edicts,” the Colony’s relations with neighboring tribes did not improve: the Indians continued to stockpile weapons they received in trade for food and other provisions, and the colonists let their guard down by not building forts and garrisons to protect against attacks. Four years after Argall issued his “Proclamations and Edicts,” the Colony suffered the Massacre of 1622, in which hundreds of settlers were killed or injured in a surprise attack by well-armed Indian warriors. Colonists had resisted Argall’s tough love, and from 1618 on he was the subject of widespread criticism, including accusations of corruption. As Martha McCartney summed it up, “when Argall died in 1625-26, he was under a persistent cloud of suspicion.”

April 1619: Samuel Argall Departs Jamestowne

It’s hard to find a Jamestowne colonist who was more active in the affairs of the Colony during its first decade that Argall. After arriving in July 1609, Argall participated in many of the seminal events at Jamestowne until he left Virginia for good in April 1619 after years of hyper-activity, as described below. Despite his service to the Colony over the course of ten years, he left Jamestowne under a cloud, after suffering much criticism of his leadership in the preceding years, and his tenure as Deputy Governor from May 1617 until he stepped down upon the arrival of his replacement, Sir George Yeardley.

Argall is remembered for his adherence to martial law at Jamestowne, and his strong-willed efforts to improve the Colony’s military preparedness. He prohibited colonists from having contact with the neighboring tribes, and restricted trade with them. For this, his tenure as Deputy Governor is considered by some historians to have been a mixed success, as he also accomplished many good things for the colonists, including his push to allow colonists to own land that previously was controlled by The Virginia Company. As one source puts it, “Argall’s administration anticipated the collapse of the Company.” After returning to England, he was knighted by King James in 1622, and died at sea in 1626.