When the Pilgrims arrived at Cape Cod in the Fall of 1620, they were immediately faced with the task of starting a new colony in North America with only the barest of essentials to sustain them as winter approved. They lived at first in makeshift shelters in what Governor William Bradford later described as the “desolate wilderness” of New England. They had only sketchy information on what might await them, but they understood that among other potential perils, they were going to be encountering native-Americans who already lived there, and who may or may not be friendly. Only one Mayflower passenger, Stephen Hopkins, had had any prior experience with native Americans, as he had been one of the original settlers of Jamestowne, where he dealt with the native tribes that inhabited the area of James River where the Jamestowne Colony was established. For all the rest of the Mayflower passengers, this was going to be a “first encounter” for them. And one of the first Indians they encountered was the man who William Bradford called “Squanto,” who died this day on November 30, 1622.

Squanto’s life story is a highly unusual one for a native American of the early 17th century. He was a member of the Pawtuxet tribe, and at a very young age he was kidnapped by an English slave trader, Captain Thomas Hunt, and in @ 1614 he was taken to Spain, where he was sold into slavery. By a miracle, Squanto was released into the custody of Franciscan friars, made his way to England (how is not known), and finally returned to New England in about 1619. During his years of enslavement, he managed to learn English, making him a rare commodity among native-Americans back in America.

When Squanto returned home, he was devastated to learn that his entire village had been wiped out by disease, and he was essentially orphaned. Having no home, he was taken in by the Wampanoag tribe, where he was residing when the Mayflower dropped anchor in Plymouth harbor. It was there that Squanto became close to the chief (“Sachem”) of the Wampanoags, Massasoit, and the two of them would become instrumental to the success or failure of the new Plymouth Colony.

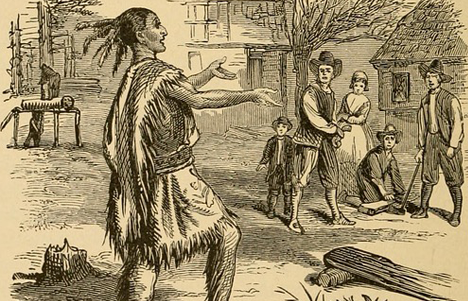

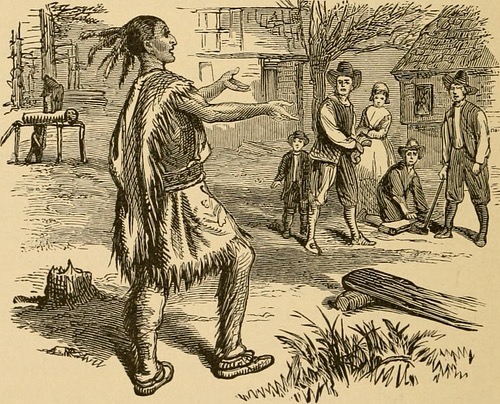

Squanto was not the first of the New England native Americans who the Pilgrims encountered—that was Samoset, a native-American who worked closely with Massasoit, and who also spoke English– but he was by far the most important. Soon after he was introduced to the English settlers in the Spring of 1621, Squanto became a fixture in the Colony, serving as a translator, guide and general helper to the colonists. Over time, he was befriended by several of the Colony’s leaders, including Edward Winslow, who travelled with him into the interior to meet with members of the Wampanoags, and to plot political strategy. Squanto proved himself to be an adept “go between” between the English colonists and the Wampanoags, and made himself indispensable, a fact that ultimately led to great difficulties as we shall see.

Squanto’s close ties to the Plymouth Colony did not go over well with some of the Wampanoags, who believed that Squanto was not always honest, and not always fairly translating, so that he was able to manipulate situations to his own personal advantage—and make himself more powerful. At one point, Squanto was accused of being part of a conspiracy with the Massachusetts and Narragansett Indians to lure the Colony’s leaders to their villages where they would be held captive, while Indian warriors would then attack the Plymouth settlement. This allegation was made by Hobomok, a Pokanoket Indian who was a close ally of Massasoit. Some historians suggest that Hobomok made the charge out of jealousy, but we will never know. What we do know is that Squanto’s reputation continued to deteriorate, and soon the leaders of the Colony decided to conduct an inquiry into Squanto’s behavior. The conclusion reached, according to Bradford, was that Squanto may have been acting in order to “make himself great” in the eyes of the local natives, and to extort money and property from them. Squanto is also said to have attempted to sabotage the peace agreement between the colonists and the Wampanoags, and to have spread false rumors that the English intended to spread the Plague into neighboring Indian villages.

Matters finally came to a head when Massasoit demanded that the Plymouth Colony release Squanto into the Indians’ custody, so that he could be executed. Bradford himself was incensed by Squanto’s conduct, and said that Squanto “deserved to die.” Yet, Bradford stood up to Massasoit and refused to turn Squanto over. Somehow, over the next few weeks Squanto and Massasoit reached an accord, and the demand that he be executed was tabled.

Squanto’s last days were spent on a trading expedition in which he served as a guide and translator. During the expedition, Squanto became ill, and died suddenly on November 24, 1622 in the area that is now Chatham, Massachusetts. Bradford wrote that he died of “Indian fever,” and that right before he died, Squanto asked Bradford to pray for him, “that he might go to the Englishmen’s God in Heaven.” The exact location of Squanto’s grave is not known, although several decades ago, human remains were unearthed that some people claimed were the remains of Squanto. Although this has never been proven, a monument to Squanto was placed there, and can still be seen today.

Squanto’s life has become the stuff of legend. In 1994, Disney Studios filmed a movie, “Squanto: A Warrior’s Tale,” that was very popular at the time. A wonderful biography of Squanto by Professor Andrew Lipman was published last year, entitled “Squanto: A Native Odyssey.” We recommend this book to anyone who wants to do a deeper dive into the life of this complicated man. Was Squanto a hero? A villain? A huckster? He was perhaps all of those and more. Whatever the truth, he played a pivotal role in the first two years of the Plymouth Colony, and for that we honor his memory today.