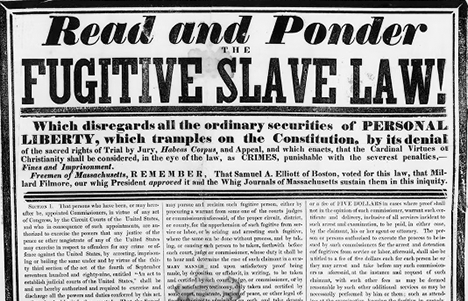

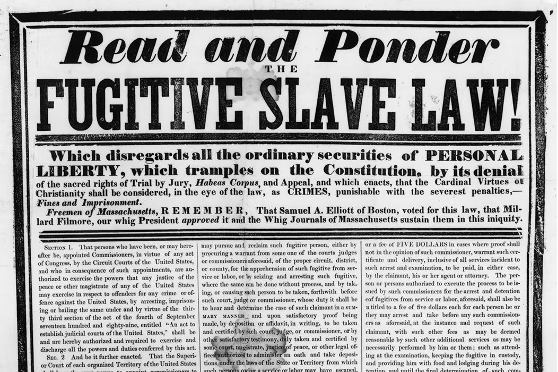

A decade before the start of the Civil War, America was in the midst of a major political crisis, triggered by the passage in 1850 of the “Fugitive Slave Act.” Intended to be part of “compromise” legislation addressing the issue of the expansion of slavery in the Western territories, the Slave Act was decidedly—horrifically—pro-slavery in its purpose and effect.

The legislation commanded that citizens of “free” states where slavery was outlawed nevertheless had a legal obligation to assist slaveholders—mostly Southern—in capturing and returning escaped slaves to their masters. The Act was officially signed into law by President Millard Fillmore on September 18, 1850 and was immediately met with fierce opposition from Northerners and other citizens who viewed slavery as a blight on American society. Passage of the Act caught many Northerners by surprise, not just hard-core abolitionists, but also average citizens who rightly saw the law as a direct infringement on their own civil rights. In retrospect, we know that the Slave Act was just the first shoe to drop—just 4 years later, Congress enacted the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which removed any restrictions on slavery anywhere, followed by the infamous Dred Scott decision in 1857. All of these events were pre-cursors of the vicious political battles that took place in the run-up to the Presidential election of 1860, and the subsequent secession of the Southern states from the Union after Abraham Lincoln took office in 1861. In this sense, the Fugitive Slave Act can be said to have been a direct cause of our Civil War.

The legislative activity leading up to passage of the Slave Act was protracted, heated, and—of course— tinged with overt racism. The political debates over slavery continued for over half a century before the Slave Act was passed. The first iteration of a slave act actually dates back to 1793, when Congress passed a Fugitive Slave Act that was honored more in the breach than enforced according to its terms. This standoff ultimate led to the “Missouri Compromise” of 1820, which drew a literal line from East to West—the famous Mason-Dixon line—above which slavery was outlawed, but preserved in the Southern states. That left open, however, whether slaves who escaped to Northern states would be deemed free persons once they crossed the line. Some Northern states, defying the 1793 legislation, passed their own laws requiring a jury trial before an escaped slave could be transported back to his or her owner (and Northern juries tended not to convict escaped slaves one these matters came to trial). Some states also barred its law enforcement officials from cooperating with slaveholders who sought the return of their “property.” In 1842, the U.S. Supreme Court intervened, siding with the anti-slavery advocates and holding that as a matter of law, the citizens of free states could not be compelled to aid in the recapture of escaped slaves.

Throughout this time period, the “abolitionist” movement was growing, although the anti-slavery Whig party never embraced the idea of total emancipation (and many Northerners were content to simply look the other way, and allow slavery to persist in the South). Leading advocates for abolition included men and women who have become famous: Frederick Douglas, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Harriet Tubman, to name a few. Yet, the U.S. Congress continued to be stalemated, and the Constitution’s “two thirds” rule the counted slaves as persons for purposes of calculating total population allowed the Southern States to be over-represented in the Congress, and have enough voting power to stymy efforts to limit or eliminate the institution of slavery. Given this political reality, Congressional leaders in both the North and South steered what they thought was a middle course.

What happened in 1850 is an excellent example of how well-meaning “compromise”—advertised as the “Compromise of 1850” — went awry. The Fugitive Slave Act was in fact part of a bundle of five legislative bills that were passed together. The other four acts were a mixed bag:

- It approved California entering the Union as a state (its constitution outlawed slavery)

- It banned the slave trade in Washington D.C.

- It defined boundaries for the new state of Texas and established a territorial government for the new Territory of New Mexico, without any limitations on slavery

- It established a territorial government for Utah, with no restrictions on slavery

The two congressional leaders who were most responsible for the successful passage of the Compromise of 1850 – Henry Clay and Stephen A. Douglas—were not zealots for the institution of slavery, nor were they vocal supporters of the anti-slavery movement. Rather, they were supporters of the Union, and believed that compromise on the issue of slavery was the only way to preserve the Union. History has judged them somewhat harshly, but at the time they had plenty of support from both ends of the political spectrum.