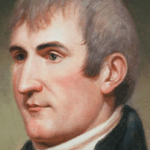

The history of the Colony of New Netherland in North America (today’s New York) is inseparable from the history of one man: Peter Stuyvesant, who served as the Director-General from 1647 to 1665, when the Colony was taken over by the English. We honor his memory today, the 353rd anniversary of his death in August 1672.

Born in 1610 in the Netherlands, Stuyvesant was the son of a Calvinist minister, Balthasar Lazarus Stuyvesant, and his wife Margaretha. At age 20, Stuyvesant entered college, but did not complete his studies. Instead, he joined the West India Company, which assigned him to a variety of foreign postings—Brazil, Curacao, Aruba, Bonaire, and St. Martin, among other assignments. His duties ranged from overseeing the Company’s commercial activities, and engaging in military operations to protect the Company’s interests, especially against the Spanish. In one such military confrontation against Spain in St. Martin, he was wounded, and his leg was amputated (and he lost the battle in the process). Thousands of images of Stuyvesant depict him as a “peg leg,” and indeed he was—he was fitted with a wooden leg, studded with silver nails.

Following the loss of his leg, Stuyvesant was assigned to take over as Director-General of New Netherland. Where his leadership skills were to be sorely tested.

Stuyvesant was a complicated man, revered by some, vilified by others, as we’ll talk about below. He succeeded William Kieft as Director General, who had been a truly terrible leader of the Colony, and who had led the Colony into a disastrous war with the neighboring Lanape and Wappinger tribes (known today as “Kieft’s War”). Due largely to Kieft’s incompetence and corruption, the Colony was in a shambles when Stuyvesant arrived in May 1647. Many of the colonists had left, and only a few hundred colonists remained.

Today, most Americans don’t appreciate how vast the Colony of New Netherland was, and the difficulties that fact created for Stuyvesant. We tend to think of New Netherland as the area that became New York City (“New Amsterdam”), but it was much more than that: the Colony encompassed lands on both sides of the Hudson River all the way north to Fort Orange (today’s Albany, NY). The Colony also extended into today’s Connecticut, Long Island, and New Jersey. Parts of this vast territory had been given by the Dutch government in 1629 to a handful of wealthy Dutch aristocrats who established “patroonships,” which were basically personal fiefdoms controlled by the owners of those lands (the most prominent example being the patroonship of Rensselaerwijck, near Ft. Orange). These “lords of the manor” posed a political challenge to Stuyvesant, since they could rule their territories without needing to have their decisions approved by the Dutch East India Company, or even consult with the Company. For Stuyvesant it became a political hot potato to manage the affairs of the Colony while trying to avoid conflicts with the Patroons.

Much has been written about the many difficulties Stuyvesant faced during his tenure in office. Among them was ongoing religious strife, some of which was of Stuyvesant’s own making. In 1657, for example, he barred Lutherans from having a church. He also tried to bar Jews from the Colony, calling them a “deceitful race,” but this attempt was stopped in its tracks by the West India Company—he was ordered to allow Jews to stay in the Colony. He also oppressed Quakers, which precipitated public protests by Quakers and their supporters.

Despite these egregious examples of Stuyvesant’s autocratic tendencies, he accomplished many things that we would applaud today. He took aggressive steps to clean up the town, stop livestock from wandering the streets, establish health and safety standards, regulate construction, and create fire brigades to mitigate the risks of fires (an ever-present threat, given that most structures in New Amsterdam traditionally had been made of wood). Stuyvesant also was responsible for instituting important political reforms that gave rise to a more democratic government structure. In the first year of his administration, he also authorized the establishment of an elected body of representatives called the “Nine Men” to advise him on colonial affairs of state. In 1649, this body took steps to remove the Colony from the control of the West India Company, and to create a more autonomous local government structure. He also led the effort to fix the boundary with the neighboring New Haven Colony, resulting in the “Treaty of Hartford.” Likewise, he led the effort—this one military—to take over the colony established by Swedish immigrants called “New Sweden,” located south of New Amsterdam on the Delaware River. After taking possession, Stuyvesant renamed the settlement “New Amstel.”

Modern historians have tended to focus attention on the more controversial side of Stuyvesant’s mindset. We’ve already talked about his intolerance of religious dissenters. More troubling still was his racist streak, which manifested in his continued support for the institution of slavery in the Colony. While Stuyvesant himself only owned two slaves, slavery was a fact of life in New Netherland until the English takeover in 1665 (and beyond).

Stuyvesant’s tenure as Director-General ended abruptly in 1664, when Engliand sent warships to seize the Colony, following King Charles II’s awarding of a charter to his brother James, the Duke of York, giving him all the lands comprising New Netherland. Stuyvesant, whose Colony was ill-equipped to wage war against the British, capitulated, and he signed the “Articles of Capitulation” by which New Netherland was transformed into “New York” (named for James). Stuyvesant remained a resident of New Netherland following the take-over, and lived out his life there.

As for Stuyvesant’s family life, he married Judith Bayard in 1645, just before he was appointed to be the Deputy-General. They had two sons, Balthasar and Nicolaes. During his tenure as Director-General, Stuyvesant acquired vast landholdings in New Amsterdam. After he stepped down in 1665, he and Judith lived peacefully at his 62-acre farm on the East Side of what is today’s Manhattan, which he named “Bouwerij,” which translates to “the Bowery.”

Stuyvesant died of natural causes in August 1642. He was buried in the family chapel, inside the grounds of St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, located in today’s East Village in Manhattan, and his burial vault can still be seen today. St. Marks is the oldest site of continuous religious worship in New York City.

In honor of his long years of service to New Netherland, there is a multitude of place names in New York bearing his name, including Stuyvesant High School, the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, and Stuyvesant Square. Reflecting the reach of the New Netherland Colony over which he presided, Bergen County, New Jersey erected a monument to his memory in 1915. That same year, a bust of Stuyvesant was placed in St. Mark’s.

And so today, we, too, honor the memory of Peter Stuyvesant, one of the most important figures in the history of the city of New York.