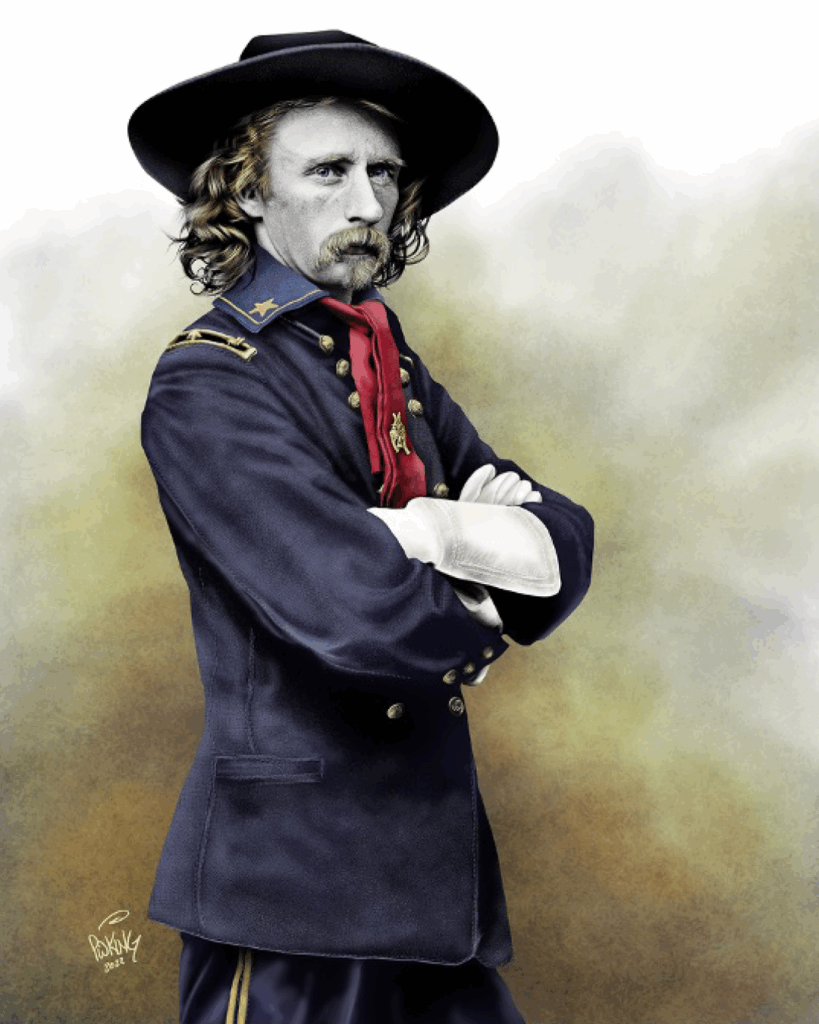

149 years ago today was a day of disaster: it was the day that General George Armstrong Custer and his troops were annihilated by Native-American armed forces led by Chief Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and other tribal leaders. The disaster was in no small due to the fatal hubris of General Custer, who over the course of several weeks had made several strategic mistakes, and grossly underestimated the fighting strength of the enemy.

General Custer’s mission in the West— which ultimately led to the Battle of Little Big Horn — was to carry out a U.S. Government mandate to eliminate the threat of Indian attacks in the western territories. Among the military leaders who carried out this mandate were at least two now-famous Union Army generals from the Civil War: William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip Sheridan, neither of whom hesitated to launch attacks on Indian villages, destroy crops, kill livestock, and capture or kill Indian leaders. Modern historians and Native American advocates often use the word “genocide” to describe the Indian Wars, which stretched back several decades prior to the Battle of Little Big Horn. In retrospect, the victory of the Indian forces at Little Big Horn was just a momentary setback in the Americans’ determined efforts to contain the Indian threat: American troops continued to pursue a “scorched earth” campaign that lasted until the main Indian leaders of the Indian Wars such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse were dead, and virtually all the tribes were relegated to living out their lives on Indian reservations.Background

The history of the Battle of Little Big Horn is in no small part the history of George Armstrong Custer. Custer had achieved his first military success during the Civil War, and his wartime exploits gained him a modicum of fame. He also married well: in 1864 he married Elizabeth “Libby” Bacon, daughter of a wealthy businessman. Libby was devoted to her husband, although some historians have suggested that their marriage was tumultuous. After the war, Custer was sent west, and Libby went with him, living in the various forts where Custer was stationed, and doing what she could to help advance her husband’s career. She later said of her choice to go west with her husband: “it is infinitely worse to be left behind, a prey to all the horrors of imagining what may be happening to one we love.”

Custer had had one set back after the Civil War, when the Army reduced his rank from “brevit” major general (a temporary rank) to Lt. Colonel. The demotion rankled him; he had come to believe his own publicity that he was a great war hero destined for great things, and the demotion did not sit well with the ambitious Custer. This partially explains his drive to achieve even greater military success in the Indian Wars, and his penchant for taking unnecessary risks and putting himself and his troops in harm’s way (one might also speculate—deep psychology here– that he perhaps was also seeking to compensate for having graduated last in his class at West Point).

Custer’s Leadership of the 7th Cavalry

After a brief interlude after the end of the Civil War, during which Custer dabbled with other possible pursuits, Custer received his appointment as Lt. Colonel in July 1866, and was given command of the 7th Cavalry Regiment. He and his troops then went west to Kansas, Colorado and what was then called “Indian Territory,” where they engaged the enemy (primary warriors of the Sioux and Cheyenne nations). His tendency to make decisions on the fly followed him, and at one point during his military duties out west, Custer decided to simply leave his regiment and go visit his wife back at the fort—a transgression for which he was temporarily suspended from duty. Custer had a mind of his own, and he was seemingly unphased by the official rebuke.

Over the next decade, Custer led his men in many battles and raids during the Indian Wars. These have been the subject of countless books and publications, and we won’t attempt to cover that subject here. In 1876, he was ordered to lead his regiment against the Sioux, with whom President Grant had unsuccessfully attempted to negotiate an agreement by which the U.S. would acquire the Black Hills of North Dakota (where gold had been discovered). Custer was thrilled to get the assignment, but he had also been ordered to testify in a corruption trial in Washington D.C. (which just so happened to involved one of President Grant’s family members). Not wanting to miss the action out west, Custer defied the order to testify in D.C., and he left to join his regiment without permission. Bad decision: he was arrested in Chicago, and President Grant re-assigned the command of the mission to Brigadier General Alfred Terry (who was play a central role in the disaster at Little Big Horn). Custer was later allowed to assume command, but only after Grant extracted a promise that Custer would operate under Terry’s direct supervision. Custer said he would do so, but immediately proceeded to ignore the condition, saying to one of his subordinates that he would “cut loose” from General Terry. And so he did, and so he started down the path of bad decisions that led to his death later that year.

The Battle

So much has been written about the Battle of Big Horn that it would be virtually impossible to condense the story into a few paragraphs. But we can point to several of the worst of Custer’s tactical decisions that led to the defeat. First, he woefully under-estimated the size of the enemy combatants. When Custer departed Fort Abraham Lincoln on May 17, 1876, he commanded approximately 500 officers and men. The Sioux-Lakota-Cheyenne force was at least double that size. Indeed, some historians believe that the total size of the Indian force was @ 1,000 warriors, while other historians claim the number was closer to 2,000 warriors. Either way, Custer’s men were grossly outnumbered—but he didn’t know that. Believing that he had the superior force, Custer arrived at Little Big Horn, saw the village, and exclaimed to his men, “boys, hold your horses, there are plenty of them down there for us all.”

A second fundamentally flawed decision Custer made was to split his forces into three battle units. He made this decision after he first saw the Indian village, and concluded that he could attack the village from three sides. Doing this, however, made it impossible for any of the units to give effective assistance to each other, and it deprived Custer of the ability to make informed tactical decisions taking into account all the battlefield conditions. In fact, Custer and his unit of 200 men had proceeded over a ridge, and he could not see that the troops under the command of Major Marcus Reno were being routed, and that Reno’s men were chaotically retreating from their position at one end of the village (in the process, Reno would see 40 of his 140 men killed in action). Reno’s retreat would later lead to charges of dereliction of duty (and drunkenness).

It was at this moment of the battle that sounds of a fierce encounter taking place over the hill could be heard. Historians speculate that it was Custer’s Last Stand that Reno and his troops heard. Yet no one took any action to go to Custer’s aid. It wasn’t until two days later that the carnage at Little Big Horn was discovered, and Custer’s mutilated body was identified. He had been shot twice, once through the head. Some historians contend that Custer committed suicide in order to save himself from torture, but there is no evidence to prove this. Most historians believe that Custer was killed on the afternoon of the first day of the battle—June 25—but there is no direct evidence, and since all of Custer’s 200 men were killed (including his two brothers, Thomas and Boston) there is no witness testimony upon which to rely.

A last example of Custer’s tactical mistakes was that he arrived at Little Big Horn before he was supposed to be there. A few days prior to the battle, Custer had met with his superior officer, General Terry, to literally map out the battle plan. They had a general idea where Sitting Bull’s village was located (somewhere between the Rosebud and Bighorn rivers). Terry ordered Custer to proceed to the Rosebud River, where he was to temporarily move his troops away from the village while Terry and his troops took a longer route to reach the Bighorn (the idea being that by temporarily moving away from the village, Custer and his men might go undetected). Then, the two battle units commanded by Terry and Custer would converge on the village. But Custer had his own ideas, and he ignored Terry’s written orders. Instead, he proceeded directly to the Bighorn River and commenced his attack before any reinforcements arrived. This was a fatal mistake. Some historians suggest that Custer shouldn’t be faulted for making that command decision given the “facts on the ground” at the time of the attack. We will never know what the outcome might have been had Custer waited, and of course history is full of examples of “Monday-morning quarterbacking.”

A final note: moments before the Indian attack that would kill Custer and all his men, Custer is said to have called a meeting with his officers. By now Custer was aware that he was outnumbered, and that Reno’s troops were in deep trouble. The group discussed the possibility of retreat, and going to Reno’s aid, but Custer scotched this idea. And so he went to his death.

The Aftermath

Little Big Horn was a major victory for Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, and it emboldened them to reject any offers for them to surrender and go live on a reservation, and thereby avoid annihilation—at least for now. By the same token, many Americans were outraged by the savagery practiced by Sitting Bull and his warriors and they wanted revenge. It took years to accomplish that, but by 1890, Sitting Bull and his people were living on a reservation, defeated and demoralized. Sitting Bull himself was killed on the reservation on December 15, 1890, in an incident that many observers would say was murder. He had outlived Crazy Horse, who had also fought with distinction at Little Big Horn. Crazy Horse was killed—stabbed by a bayonet– on September 5, 1877, while he was being transferred from his village to a meeting at Fort Robinson.

The “Legacy”

The tragedy at Little Big Horn was just one of scores of conflicts during the Indian Wars that brought death and destruction to both sides of those wars. The killings of American soldiers at Little Big Horn by Indian warriors (hundreds of American soldiers died) was matched years later by the Wounded Knee Massacre in December 1890, when U.S. troops killed over 250 Indian men, women and children, an attack that many historians point to as the final chapter in the story of the conquest of the West. If there is a “legacy” to derive from the Battle of Little Big Horn, it is an elusive one.