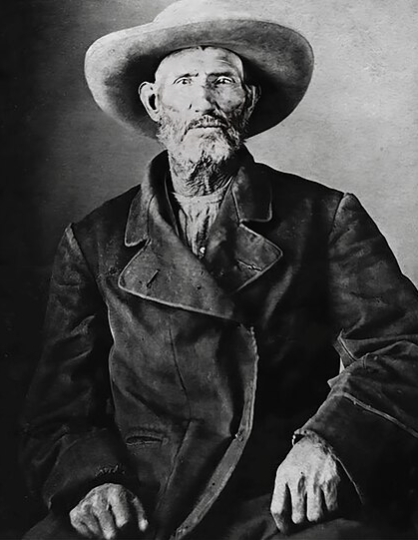

When we think of the early settlers of the American West, invariably our minds conjure up the image of intrepid “mountain men” who crossed the Rocky Mountains, battling the elements, fought with hostile Indians, and faced other threats to life and limb. Before the arrival of railroads—or even roads—there was a class of men who led that life, living off the land, and making a living by trapping beavers, hunting buffalo, or mining for precious metals. Most of these men lived and died anonymously. Some became known for their trailblazing skills, and were sought out to lead expeditions across the mountains. Some even became famous. One of the most famous of such men was Jim Bridger, born this day on March 17, 1804.

Bridger was not a “native” westerner. He was born into a decidedly eastern family in Richmond Virginia, where his father worked as an innkeeper. While still a teenager, Bridger and his family moved to St. Louis, which had become a thriving city after the Lewis & Clark Expedition and the Louisiana Purchase opened up the western territories to settlement. Bridger never went to school, and was illiterate all his life. With no immediate prospects, he decided to join a fur trapping expedition in 1822, and the rest is history. Over the course of his career as a trailblazer, he led a number of major western expeditions, including in the Yellowstone region, and the Great Salt Lake. He established his own trading post and fort, called “Fort Bridger,” which today is a historical landmark. Among his most important expeditions was the Stansbury Expedition in 1850, which surveyed the vast area that became the Utah Territory. Bridger’s path-finding skills were extraordinary, so much so that some of the routes he carved out became known as “Bridger Pass” and “Bridger Trail.” Later, he served as a scout for American troops during Red Cloud’s War, and was present at Fort Kearney when the infamous Fetterman Fight took place in 1866. He was

As was true of many mountain men, Bridger rarely lived in a “civilized” community. He had several Native-American wives over the years, and with them he fathered a number of children. Two of his wives were from the Shoshone tribe, while a third wife was from the Flathead tribe. Because of the itinerant nature of his work, Bridger send some of his children east to be schooled. By the 1870’s only one daughter, Virginia, was still alive, and when Bridger began to slow down, he chose to move east to live on a farm he owned, and to have Virginia care for him. Bridger passed away in July 1881 at the age of 77—a remarkable lifespan for someone who put himself in harm’s way for almost half a century.

So, today we honor Jim Bridger, a man whose trailblazing skills defined an era, and who is remembered today for his major contributions to the exploration and settlement of the West.