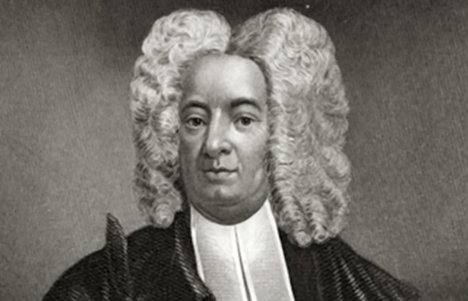

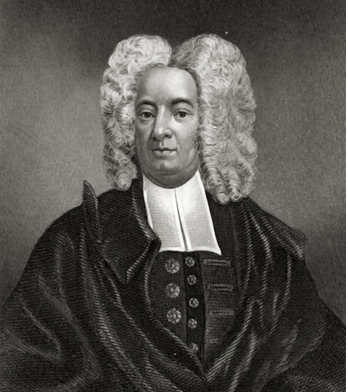

A major church leader in early America was Cotton Mather, who died this day on February 13, 1728 at the age of 65. He was one of the most controversial Puritan clerics of his era, known for his many books, papers and sermons on the theology of the Puritan faith, but also known for his strident attitudes towards non-believers of all kinds– “heretics,” he would call them, or worse. Most infamously, he was a strong defender of the Salem Witch Trials in 1692-93, and went so far as to publish a book, Wonders of the Invisible World, in which he sought to justify the trial and execution of the accused witches. After eleven innocents were hanged in September 1692, he wrote to the Judge who presided over the trials to congratulate him for “extinguishing of a wonderful piece of devilism as has been seen in the world.” While it’s true that colonists in that era believed in witchcraft, and there are many other examples of executions of accused witches in the historical record of New England, Mather’s damnation of the accused Salem witches has gone down in history as uniquely noxious, and historians have judged him harshly as a consequence.

Mather was born in 1663 in Boston, a third-generation New Englander who, like his father Increase Mather, attended Harvard College in 1674—at age eleven!! After graduation, he went straight into church life, and was ordained in 1685 at the age of 22. The next year he married 16-year-old Abigail Phillips, and they had eight children together before Abigail died in 1702. Mather had six more children with his second wife, Elizabeth Hubbard. When she died in 1713, Mather married a third time, to Lydia Lee George, but they had no children. Only two of Mather’s many children survived him.

Although a man of the cloth, Mather did not shy from becoming involved in Massachusetts Bay Colony politics, most prominently the “Revolt of 1689.” The crisis arose when King James II revoked the Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company, and appointed Sir Edward Andros the new Governor of the Bay Colony. Andros proceeded to invalidate land grants previously issued by the Company, and Mather became involved in the colonists’ resistance to Andros. During the crisis, Mather was threatened with arrest, but that did not deter him from continuing to challenge Andros’ policies, and he is believed by some historians to have authored an inflammatory pamphlet, the “Declaration of the Gentlemen, Merchants and Inhabitants of Boston and the Country Adjacent.” The outcome of his efforts, however, was most likely viewed as a defeat for mainstream Puritan colonists: in 1691, the King granted a new charter that mandated religious toleration, which ran against the strict Puritan theology that non-Puritans were heretics. Ironically, the first Governor appointed under the new charter was a member of Mather’s church. Mather later crossed swords with another Massachusetts Governor, Joseph Dudley. Over time, Mather’s political stature was greatly diminished.

Throughout his life, Mather was a Puritan thought-leader, and wrote over 300 books and pamphlets, most famously the Magnalia Christi Americana, published in 1702. By then, Mather’s Puritan views had softened, and he expressed greater tolerance for non-Puritan believers such as Baptists, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists. Yet, he frowned upon the liberal educational trends at his alma mater, Harvard College. After he tried and failed to be named President of Harvard, he threw his support to rival Yale College, which featured a more conservative course of study.

Besides his religious and political pursuits, Mather involved himself in a wide range of other activities, including the promotion of smallpox inoculations, the study of the science of plant life, and the cause of bettering the living conditions of enslaved persons (he had been a slaveholder himself, but he was not an advocate for emancipation). In some respects, he might be considered a Renaissance man, but with the passage of centuries, Cotton mostly is remembered for his extreme Puritan belief system.

So, today we honor the memory of Cotton Mather, who died this day on February 13, 1728. He is buried at the Copps Hill burial ground in Boston.