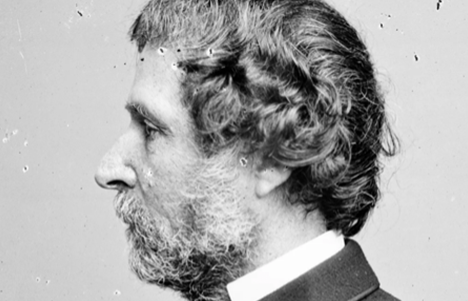

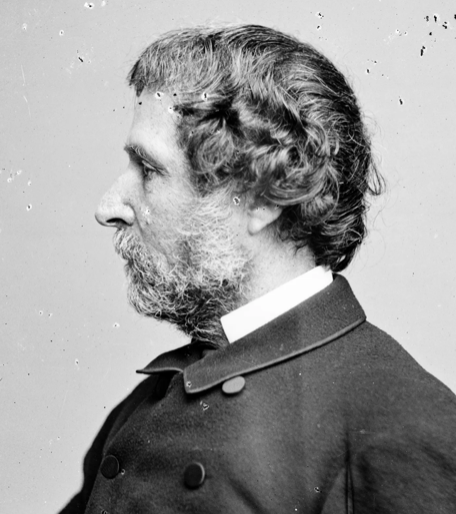

Born this day in 1813, Major-General John C. Fremont was one of the most popular men in America in the mid-1800’s: a soldier, an explorer, a gold speculator, a territorial Governor, a U.S. senator, and a leading candidate for President of the United States. The popular press lionized him, and his wife Jessie Hart Benton, daughter of the prominent Washington politician Thomas Hart Benton, promoted John as a conquering hero of the West—nicknamed “The Pathfinder.” Fremont’s life story epitomizes the pioneer spirit of his era—boldly marching towards the future and letting nothing get in his way (including Native-Americans). He gained his national reputation from a combination of ruthlessness and hubris, often adopting a “take no prisoners” attitude towards his adversaries.

Fremont was born out of wedlock in 1813 to Anne Beverley Whiting, who was married to Major John Pryor, but was involved in an extramarital affair with Charles Fremon[t]. When their affair was discovered, they fled to Georgia, where their son John was born. When John was 5 years old, his father died, and the family moved to South Carolina. Within a few years Fremont embarked on a series of adventures, including a stint in the fledgling U.S. Navy in the 1830’s, followed by an appointment to serve in the U.S. Topographical Corps as a surveyor. No doubt it was this job that sparked his interest in exploring and surveying the territories of the West, an avocation he pursued in the 1840’s, and for which he achieved great notoriety “back east.” He led three major expeditions during the period 1842 to 1846, the last of which embroiled him in warfare against Native-American tribes in California and Oregon, and led to the deaths of hundreds of Indian men, women and children. Among his men in those conflicts was Kit Carson, whose life he saved during a battle with the Klamath Indians in 1846.

All this fighting prepared Fremont well for the Mexican-American War of 1846-48, in which he led the troops that seized the California territory from Mexico in 1846/47, following which Fremont declared himself the Military Governor. His aggressive tactics led to a court martial and conviction in 1848. Thankfully for Fremont, President James Polk commuted his sentence (but he was not exonerated). Fremont continued with his explorations in 1848-1849, then became Senator of the new state of California in 1850. By 1856, Fremont was so popular that he was nominated for the Presidency of the United States by the new Republican party. Fremont lost to James Buchanan, who bested Fremont in the popular vote by @ 500,000 votes.

Fremont saw significant action in the Civil War, serving initially as a general in the Department of the West. Among his officers was Ulysses S. Grant. His battlefield tactics were sometimes questioned, as were his administrative decisions. At one point he was accused of misconduct by President Lincoln after Fremont announced that he was emancipating all slaves in Kentucky. Lincoln decided not to court-martial Fremont, but relieved him of his command of the Department of the West. Fremont sat out the rest of the war in New York City, after refusing a post in the Army of Virginia. In 1864, Fremont’s supporters, outraged over Lincoln’s treatment of Fremont, nominated him for President as the candidate of the “Radical Democracy Party.” Fremont lost, of course, and his political fortunes faded. For a period of time he lived in Arizona, where he served as Territorial Governor from 1878 to 1881. After retiring from politics, he and his wife Jessie moved to Staten Island, New York, where he died in April 1890 at the age of 77.

Today we honor the memory of John C. Fremont—once a towering figure in American history, whose legacy is one of heroic deeds and fatal miscalculations.