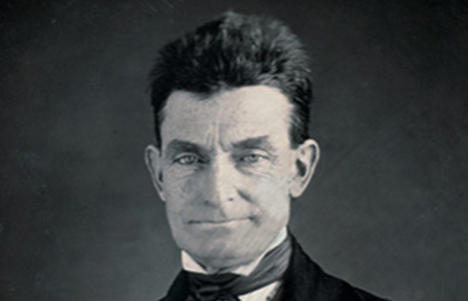

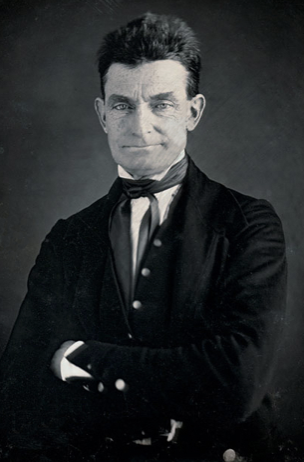

Fifteen months before the American Civil War commenced with the shelling of Fort Sumter in April 1861, one of the most memorable events in the history of the abolitionist movement in the United States took place—the execution by hanging of John Brown on this day, December 2, 1859. Brown had been an outspoken advocate for the emancipation of enslaved African-Americans everywhere, and for the abolition of slavery. His position—and those of other abolitionists—ran counter to future-President Abraham Lincoln’s carefully-calibrated presidential campaign position that slavery might be preserved in the Southern states, but prohibited everywhere else. Some historians argue that Brown’s tactics were those of a martyr in the making—crazy, perhaps– yet none can argue that his ultimate goal of freeing the slaves wasn’t a noble one.

John Brown was born in May 1800 to Owen and Ruth Brown, “Northerners” then living in Connecticut, both of whom were descendants of Revolutionary War patriot ancestors. In the small world department, when the Browns moved to Ohio in 1805, the family became friends with Jesse Grant, whose son Ulysses would go on to become the Commander-in-Chief of the Union Army, and later President of the United States. At the time, Ohio was a pro-abolition state, and Owen Brown himself was a staunch abolitionist. John Brown also was schooled by an abolitionist teacher. It was in this environment that John Brown developed his own views on the institution of slavery. After a brief sojourn to New England to attend college (he never graduated), Brown returned to Ohio, where he married Dianthe Lusk in 1820; they had seven children before Dianthe died in 1832. He remarried the following year to Mary Ann Day, with whom he had another 13 children (!!).

Brown’s anti-slavery activism began in earnest when he moved to Pennsylvania in 1825. There, he became part of the Underground Railroad, helping escaped slaves coming North from Virginia. Over the next decade, he formed close relationships with other leading abolitionists, while earning a living in various business pursuits. He also held several civil service posts to which he had been appointed by Presidents John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. Brown and his family returned to Ohio in 1836, where he became more militant in his abolitionist views, while falling into debt and declaring bankruptcy in 1842. His involvement in the abolitionist movement accelerated when he moved to Massachusetts in 1846, and during the next 12 years, he became an increasingly vocal advocate for the violent overthrow of the institutions of slavery. It was during this period that the U.S. Congress enacted several laws intended to appease Southern slave states, such as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which further inflamed Brown’s thinking that only armed insurrection would overcome America’s tolerance of slavery. Perhaps aware that his actions might some day lead to his own death, he bought a home in North Elba, New York where he deposited his family while he continued to pursue his anti-slavery activities in other parts of the country. It was at his New York home that Brown was buried following his execution in December 1859; today it is a National Historic Landmark.

The last years of Brown’s life were spent in various violent conflicts over slavery, including his participation in the Pottawatomie Massacre of 1856, part of the deadly years of open warfare in Kansas that became known as the “Bleeding Kansas” years— essentially a local civil war fought over the hotly-contested issue of whether the Kansas Territory could become a slave state (a possibility signaled by the earlier Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, by which Congress authorized the people of Kansas to decide whether they wanted slavery or not). All of this culminated in Brown’s history-making attack on Harper’s Ferry on October 16-18, 1859. Brown and his men had intended to seize the armory there, and free all the slaves. But the plan was botched, and Brown and his men were trapped in a nearby engine house. When given the chance to surrender to a company of U.S. Marines who surrounded him, Brown famously said “no, I prefer to die here.” That did not happen. Instead he was captured, put on trial, and quickly found guilty of treason on November 2, 1859. He was hanged exactly one month later, on December 2, 1859. His last words, written but not spoken, were prophetic:

“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without much bloodshed it might be done.”