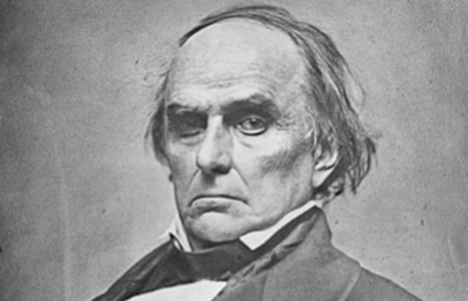

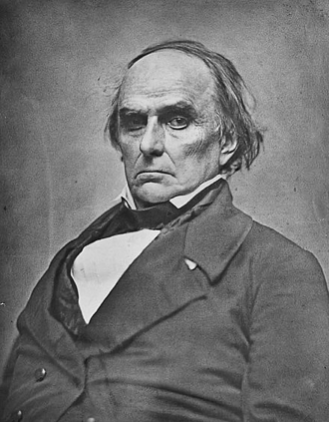

One of the most important political leaders of the early 19th century, and one of America’s greatest orators, Daniel Webster died this day on October 24, 1852.

He played a prominent role in the federal government’s decades-long battles over settlement of the Western Territories, and most famously as Secretary of State overseeing the series of legislative acts that became known as the Compromise of 1850. The Compromise legislation consisted of a series of statutes, including laws that i) approved California’s statehood; ii) enacted the Fugitive Slave Act; iii) banned the slave trade in Washington D.C.; and iv) created the Utah Territory, without any restrictions on slavery.

Webster’s political views on slavery evolved and changed, but as a leader of the Whig party he sought to appease Southern interests, and to accommodate the institution of slavery. The Compromise of 1850 did little to solve the dispute between North and South, but essentially delayed things. Northerners were repelled by the Fugitive Slave Act, which compelled Northerners to cooperate with slaveholders seeking to capture and return run-away slaves. Southerners believed Congress should have overtly allowed slavery in the new territories, and many Southern political leaders contended that the legislation violated states’ rights. Webster supported the legislation, believing that it would foster better relations between Northern and Southern interests on matters pertaining to Western expansion. He did not live long enough to see how wrong he was. Just two years after he died, Congress enacted the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which was perceived to open the floodgates to slavery in the West.

Webster’s career was otherwise impressive. He was a young congressman in New Hampshire and Massachusetts before becoming Secretary of State under three Presidents. As a lawyer, he also appeared regularly in the U.S. Supreme Court. Originally a Federalist, he was a strong supporter of President John Quincy Adams. He later formed the Whig party, which opposed Andrew Jackson (a slaveholder himself). As a senator in the 1840’s, however, he led a faction of the Whig party that sought to appease Southern planters. His implicit support of slavery has been the subject of countless debates by scholars, and his reputation remains tarnished by his studied refusal to condemn slavery. On many issues, he waffled, and often sought a middle ground in order to avoid damage to his political aspirations (he unsuccessfully ran for President in 1836). One historian wrote that Webster “was a thoroughgoing elitist—and he reveled in it.” Whether the criticism was fair or not, Webster was regarded by his peers as a superior intellect, and a compelling public speaker capable of capturing the hearts and minds of the country. Perhaps for this reason, he was the main speaker at the laying of the cornerstone at the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill. This and other of his speeches have gone down in history as among the greatest patriotic addresses from an American political leader.

Webster’s personal life was that of a well-educated, wealthy landowner, and family man. He had seven children by two wives, one of whom, his son Fletcher, was killed in the Second Battle of Bull Run. Webster was alleged to have carried on an extra-marital affair for several years, but that has not been proven. He was a long-time member of the Congregational Church, and is believed to have been a devout Christian. On October 24, 1852, he died of cirrhosis of the liver at his estate in Marshfield, Massachusetts, where he is buried in the Winslow Cemetery. We honor his memory this day.